The following is an excerpt from The Queer Film Guide by Kyle Turner, an upcoming book that highlights the 100 greatest and most important LGBTQ+ films throughout the history of cinema. In this excerpt, Turner reflects on 1992’s The Living End, a dark, queer roadtrip movie from seminal filmmaker Gregg Araki.

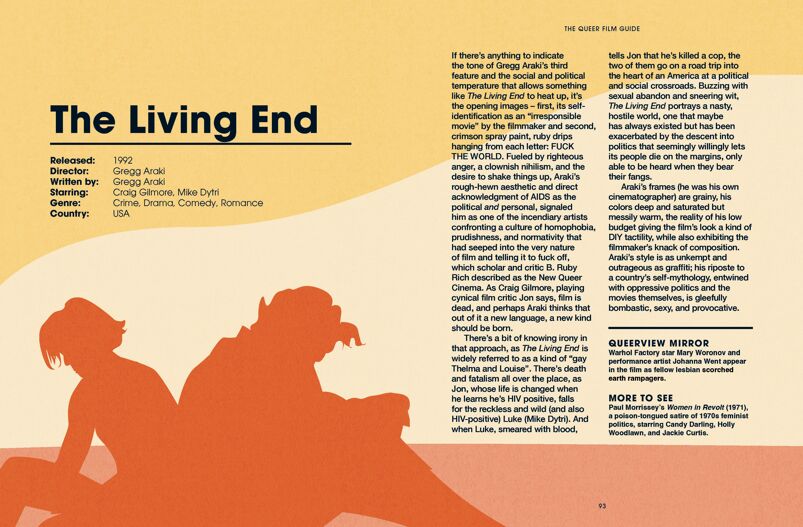

If there’s anything to indicate the tone of Gregg Araki’s third feature and the social and political temperature that allows something like The Living End to heat up, it’s the opening images—first, its self- identification as an “irresponsible movie” by the filmmaker and second, crimson spray paint, ruby drips hanging from each letter: F*CK THE WORLD.

Fueled by righteous anger, a clownish nihilism, and the desire to shake things up, Araki’s rough-hewn aesthetic and direct acknowledgment of AIDS as the political and personal, signaled him as one of the incendiary artists confronting a culture of homophobia, prudishness, and normativity that had seeped into the very nature

of film and telling it to fuck off, which scholar and critic B. Ruby Rich described as the New Queer Cinema.

As Craig Gilmore, playing cynical film critic Jon says, film is dead, and perhaps Araki thinks that out of it a new language, a new kind should be born.

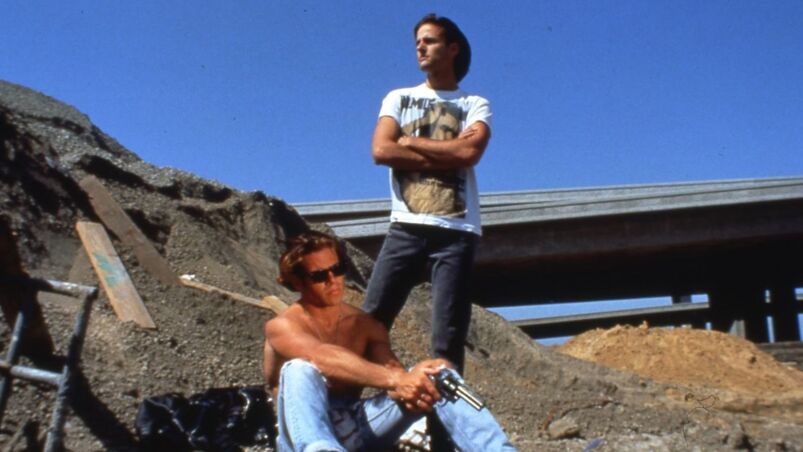

There’s a bit of knowing irony in that approach, as The Living End is widely referred to as a kind of “gay Thelma And Louise.” There’s death and fatalism all over the place, as Jon, whose life is changed when he learns he’s HIV positive, falls for the reckless and wild (and also HIV-positive) Luke (Mike Dytri).

And when Luke, smeared with blood, tells Jon that he’s killed a cop, the two of them go on a road trip into the heart of an America at a political and social crossroads.

Buzzing with sexual abandon and sneering wit, The Living End portrays a nasty, hostile world, one that maybe has always existed but has been exacerbated by the descent into politics that seemingly willingly lets its people die on the margins, only able to be heard when they bear their fangs.

Araki’s frames (he was his own cinematographer) are grainy, his colors deep and saturated but messily warm, the reality of his low budget giving the film’s look a kind of DIY tactility, while also exhibiting the filmmaker’s knack of composition.

Araki’s style is as unkempt and outrageous as graffiti; his riposte to a country’s self-mythology, entwined with oppressive politics and the movies themselves, is gleefully bombastic, sexy, and provocative.

QUEERVIEW MIRROR: Warhol Factory star Mary Woronov and performance artist Johanna Went appear in the film as fellow lesbian scorched earth rampagers.

MORE TO SEE: Paul Morrissey’s Women In Revolt (1971), a poison-tongued satire of 1970s feminist politics, starring Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn, and Jackie Curtis.

In The Queer Film Guide, each selection is accompanied by striking illustrations by Andy Warren, which you can preview below:

About The Queer Film Guide:

Beginning with early trailblazers like Different from the Others, Kyle Turner has selected 100 of cinema’s greatest queer films to guide you through the eras. From Hitchcock’s Rope and cult classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show through the New Queer Cinema movement of the 90s to the present day, where LGBTQIA+ narratives have increasingly made their way into the mainstream and dominated award seasons with films like Carol, Tangerine, and Moonlight.

From scrappy auteurs to Academy Award winners, The Queer Film Guide celebrates LGBTQIA+ stories and artists, offering a fresh take on what defines great cinema, and lending a voice to the diverse creators and characters who have shaped the artform.

Kyle Turner is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn, who writes on films old and new, queer cinema and music videos. He is particularly interested in queerness and sexuality in pop culture, and the way in which desire manifests on screen and shapes audience desire. He is a contributor to Paste Magazine and his writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Village Voice, Slate, Playboy.com, GQ, NPR, Teen Vogue, and elsewhere.

The Queer Film Guide publishes May 16, and is available for pre-order through publisher Smith Street Books.

dbmcvey

This seemed revolutionary when it came out. I haven’t watched it in years but it was amazing!

nm4047

I thought The Living End was a punk band. Also from the very early 90’s 🙂

Kangol2

The movie debuted in 1992. The band debuted in 1994. Ergo, the movie predated the band.

abfab

Done with guns. And it’s still Hollywood’s and America’s favorite prop. I can’t.

Fahd

The Living End was a good film worth rewatching. What does it mean to be a “seminal filmmaker” (see intro at top)? A film might be referred to as “semincal”, but can a person be “seminal”? I get this is Queerty and semen, etc., but…..

still_onthemark

Maybe Gregg Araki is so full of cum he practically explodes if you touch him!

Kangol2

“Seminal” as in “germinal” or “foundational.” You know, from “semen,” the Latin word for “seed”? The word’s multiple connotations are worth using the term in this regard.

FreddieW

Never heard of it. The gay road trip movie I’ve watched over and over is “The Trip”.

Kangol2

It was a landmark film when it came out, The other thing about it is that it deals openly with being openly gay and HIV positive, which was a huge deal back then.

dbmcvey

“The Trip” is also a very good movie, but very different than this one and made a decade later.

Mattster

I really liked this movie, it had a lot to say and broke many of the stereotypes common in gay movies at the time. Most people I talked about it with did NOT really like it. I think because it had a lot of anger, which made many people uncomfortable.

It really paved the way for a lot of queer filmmakers.