A promotional image from ‘Queer for Fear.’ Photo courtesy of Shudder.

Draped in a floor-length white gown, sporting a precisely stitched jawline and blowout hairdo with that now-famous ripple of white, the Bride of Frankenstein catches her first breath of life, her eyes darting around the laboratory. The Monster descends a staircase, hand outstretched. “Friend?” he beckons. She shrieks in terror, turning away. The subtext: “Oh no, I know this man is not for me!”

The Monster’s bride is “one of the most explicit queer-coded characters to exist,” says producer-director Bryan Fuller, whose four-part docuseries Queer for Fear premiered this month on Shudder. The premise of a woman rejecting what society expected at the time — marriage to a man — is queer even by today’s standards.

“There’s something about The Bride of Frankenstein as kind of the ultimate queer woman who chooses her own path and rejects heteronormativity,” Fuller tells INTO. “And about that story being told by a queer man asking the question, ‘What if she doesn’t like him for reasons that are, you know, her own?’” Fuller loves The Munsters for a similar reason — feeling connected to characters who don’t belong just like gay children don’t. He says that James Whale’s interpretation and direction of a queer woman make “perhaps the most iconic queer hero-monster of cinema.”

Even though mainstream media has often pigeonholed queer representation as an afterthought in horror over the decades, queer writers, filmmakers, and actors birthed the genre. Mary Shelley, considered the “mother of horror” and writer of the first science fiction novel, Frankenstein, was bisexual, and its film director, James Whale, openly gay. Without Shelley’s writing and the queer filmmakers that jumpstarted Hollywood’s love affair with monsters and horror, we wouldn’t have the genre as we know it today.

So why have there been such queerphobic stereotypes in the genre, despite the fact that the early years of horror were queer as heck, and everyone making them knew it? One interpretation is that horror plays off people’s fears, and in 1930, what was more frightening than queerness? It’s often positioned, in traditional horror, as being akin to the death of morality and all things holy. This moral panic permeated society in the early 20th century, infiltrating the genre’s cinematic evolution despite the presence of LGBTQ creators.

We’re in an age where gay characters and queer storylines are fighting their way back into the genre.

Early horror movies were created by queer filmmakers with queer source material as their inspiration. However, the constraints of society closed in and squashed that inherent and oftentimes explicit queerness after 1934, when the Hays Code became fully enforced. Because the code stipulated that any characters with a hint of queerness needed to be moralistically “punished” or killed off, the genre began to develop harmful stereotypes and tropes pertaining to queer people, like the “bury your gays” trope. But now, we’re in an age where gay characters and queer storylines are fighting their way back into the genre. This complicated history poses a tricky task for today’s filmmakers and fans to continue enjoying scary movies and creating meaningful frights.

Yet after decades of queer theorists reading into horror films, filmmakers are finally exploring queerness out in the open, without having to bury it in subtext.

The Gay History of Classic Horror

The earliest horror movies date back to French filmmaker and illusionist Georges Méliès in the 1890s, but it wasn’t until decades later, in 1931, that Universal Studios released Todd Browning’s Dracula, followed by Whale’s Frankenstein that same year. They weren’t meant to start a whole franchise of Universal Studios Monsters, but with their success — in large part due to American audiences’ need for a diversion from the Great Depression — the studio started churning out monster flicks.

Whale, who lived openly with his partner, producer David Lewis, for 23 years, directed Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, and The Bride of Frankenstein, which co-starred lesbian actress Elsa Lanchester. Whale was an early major player within the Universal Monsters franchise. Shelley’s queerness seeps through the source material, reflecting a monster created outside of society’s standards who is eventually chased by a mob of angry, pitchfork-carrying villagers. And having a gay director behind the film adaptation of Shelley’s queer story was the best way to bring it to life. The Frankenstein story has had such queer resonance through the years that it’s inspired queer and trans art around our identification with the monster.

Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, was also gay and deeply closeted, having witnessed the demise of fellow writer Oscar Wilde. Stoker even married Wilde’s ex-girlfriend Florence Balcombe in 1878, a union that lasted until his death. Dracula desires both men and women in his hunger for blood. While it doesn’t have to do with sex to the naked eye, that bisexual desire is not lost.

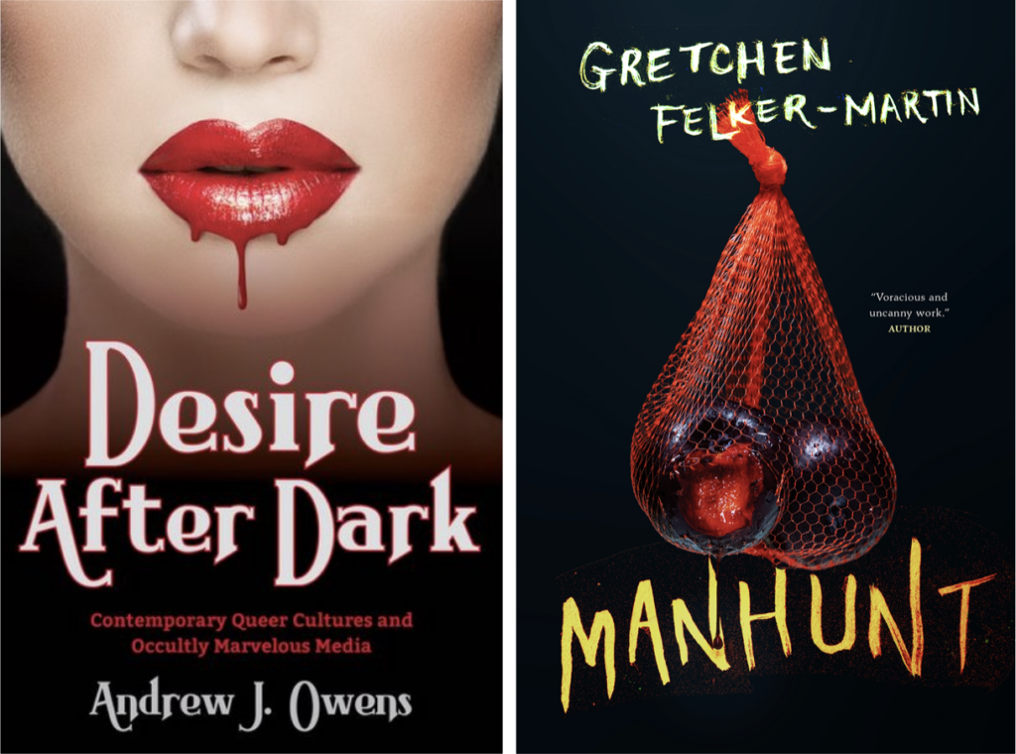

“There was something just inherently, in the sort of act of vampirism itself … sort of seductive and sexy about that. Like, you’re biting somebody on the neck,” says Dr. Andrew Owens, a lecturer at the University of Iowa and author of Desire After Dark; Contemporary Queer Cultures and Occultly Marvelous Media, who specializes in media and queerness within the horror genre.

Owens points out that vampires are an “equal opportunity employer” when it comes to who they’ll bite for blood. “And so if we take that, and then combine it with the sort of erotic aspect of biting as a sexual act, then it’s sort of like, how do we not read that as queer writers? It’s right there,” Owens tells INTO.

Dracula was released prior to the passing of the Hays Code, strict film guidelines named after Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, which prohibited sex, profanity, nudity, gratuitous violence, and — of course — homosexuality.

The code was implemented in 1921, but it wasn’t fully enforced when it came to homosexuality, sex, and drugs until 1934. Once that happened, and until a Supreme Court decision ruled it unconstitutional in 1952, all implicit and explicit queerness on screen was banished. During this era, if a filmmaker wanted to have a gay character in a movie, they had to use harmful stereotypes to “queer code” them without explicitly saying or showing they were gay. The Hays Code allowed “sexual perversions” to be shown onscreen as long as they were punished at the end, which allowed filmmakers like Whale to populate their films with queer characters as long as they were killed off in the final act.

Even decades after the Hays Code stifled explicitly queer moments in film, creators pushed the boundaries. While studying for his Ph.D. at Northwestern University, Owens traveled to the Charles E. Young Research Library at UCLA for archival research and found documents in their Special Collections from Dan Curtis, executive producer and showrunner of the late 1960s gothic soap opera Dark Shadows. This fits right in with Owens’ horror obsession, which has been lifelong and started with vampires; he startled his local librarian at age seven when he specifically asked for the Bela Lugosi Dracula.

Owens found in Curtis’ documents a corporate memo from ABC to Curtis, asking to “adjust this line of dialogue to suggest that there is no sexual relationship between these two men.” This type of explicit queerness in a show’s script was exactly what Owens was searching for; he said he “almost fainted in the archive room.”

Unpacking ‘Bury Your Gays’ and Other Homophobic Horror Tropes

Horror films eventually began to introduce more explicit queer characters, but hostility toward the queer community continued to be prevalent, fueled by what films were allowed and not allowed to show on screen, societal events such as the Lavender Scare of the 1940s and ’50s. Filmmakers started leaning into religious America’s fear of immorality, and social and moral panic took the place of representational panic on screen. Harmful, long-lasting stereotypes — such as the transphobic “killer man in a dress” theme — emerged, and tropes were established that positioned the queer community as disposable.

Filmmaker Kimberly Peirce (Boys Don’t Cry; Carrie, 2013 remake), who also appears in Fuller’s Queer for Fear, draws a similar parallel. Speaking at the recent AMC Networks Summit panel “Horror as a Safe Space,” Peirce said, “We found ourselves feeling like monsters, feeling horrified and finding ourselves reflected in these classics [referencing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Frankenstein, Psycho, etc.]. And that’s really extraordinary.”

As the genre evolved, the dreaded “bury your gays” trope emerged, in which one of the few (or only) queer and/or marginalized characters is killed off early. As Haley Hulan wrote in their 2017 journal article “Bury Your Gays: History, Usage, and Context,” it’s mostly done now to further the plot along, add shock value, or to symbolically punish queerness. However, when it first started in 1934, the trope was a way to include queer characters when they otherwise wouldn’t be allowed (thanks to that damned code again). It wasn’t always used in the harmful context it is now, but as Hulan pointed out, modern-day usage of the trope is completely unnecessary.

A significant example of this in modern times is when Buffy the Vampire Slayer killed off Tara, Willow’s girlfriend and half of one the first lesbian relationships on television, in its sixth season. It wasn’t by a demon or vampire, but a gunshot from the incel Big Bad, Warren Mears. The murder is still a massive sore spot for queer Buffy fans and shows an instance where a well-liked lesbian character died to add a shocking twist and narrative push for Willow to become evil for the latter half a season.

But “bury your gays” isn’t exclusive to horror. As Hulan wrote, it’s been around for 125 years and spans genres and mediums. In fact, filmmaker and director of 2022’s Master, Mariama Diallo, tells INTO that it’s more of a plot device in drama than it is in horror, where everybody has a fair shot at dying.

“[The] ‘bury your gays’ trope is interesting because, for me, it’s something that extends beyond,” Diallo says. “It bleeds into drama … it doesn’t just exist in the horror sphere. In fact, I feel like it almost is at its most rank just in your run-of-the-mill dramatic story.”

Glaring transphobic tropes also emerged as the horror genre latched onto the fears of cishet audiences. And as gay and lesbian representation started to become slightly more embraced in Hollywood, trans people, specifically trans women, became the next “boogeyman” in horror.

Specifically in horror, the trope of cross-dressing men or transgender characters ending up as killers is a harmful symbol of anti-trans rhetoric. Psycho (1960), along with William Castle’s copycat film Homicidal (1961), were among the first films to advance this trope. In Psycho, Normal Bates dons a wig and dress, pretending to be his mother while murdering the women who he finds attractive.

The aforementioned “killer man in a dress” figure would be reprised endlessly in the 1980s and ’90s in films like Dressed to Kill, Silence of the Lambs, and Raising Cain. There’s also Sleepaway Camp, which features one of the most well-known twists of this kind. [Spoiler Alert!] The ending of the 1983 summer camp slasher reveals that Angela is the killer only to further disclose that Angela is actually her twin, Peter, via an exploitative shot of her naked body. It’s a bit more complex than just a brother taking his sister’s “false” identity; it’s implied Angela is trans but, in keeping with trans characters at the time who sprung out of the cis imagination, her transness exists more as an added detail for shock value.

“Obviously, growing up in the ’90s, I was exposed to a ton of deeply transphobic TV, film, and literature, and so I’m intimately familiar with being explicitly degraded by art that I love, that’s really personally important to me,” horror author and film critic Gretchen Felker-Martin tells INTO. Referencing The Silence of the Lambs film adaptation, she says, “The infamous scene where Buffalo Bill tucks and poses is so intensely painful to watch.”

“There’s a push and pull to my relationship to the history of trans people’s inclusion in horror. I think the key difference is that my work is for a trans audience. I’m writing specifically for trans people.” — Gretchen Felker-Martin

Felker-Martin’s book, Manhunt, dismantles this narrative, depicting a post-apocalyptic world where the three main characters, who are trans, have to fight to survive more than just TERFs and feral men. She says that her work is in direct response to what she grew up watching. “It’s pushing back against it, but it’s also descended from it because many of those hateful images were the first time I ever saw myself on screen,” she says. “There’s a push and pull to my relationship to the history of trans people’s inclusion in horror. I think the key difference is that my work is for a trans audience. I’m writing specifically for trans people.”

Outside of individual tropes that harm sectors of the queer community, an entire era of horror was rooted in the early years of the AIDS epidemic, which sparked new iterations of the original queer demons: vampires. The 1980s exploited audiences’ fear of contaminated blood and monsters who — at least during the day — looked just like them. Vampires “passed” as humans to slink around for their next meal, becoming a part of the terror. How do you know who’s a vampire (or gay), and how do you know if they will kill you or turn you into an undead monster (or have HIV)? You don’t. Owens says that different vampire films of the time — The Hunger, The Lost Boys, and Near Dark — show that this fear of being struck with the disease plagued all walks of life, whether in the city or in the middle of nowhere. “That sort of fear of blood exchange becomes very obvious in ’80s horror,” Owens says.

He does point out, though, that while vampire horror was a big purveyor of this panic, it wasn’t the only horror subgenre to do so. Owens says that one of the more “obvious” AIDS parallels appears in David Cronenberg’s 1986 film The Fly. The film stars Jeff Goldblum as scientist Seth Brundle and Geena Davis as Ronnie Quaife, a journalist who Brundle wants to exclusively cover his new experiment (and with whom he develops a relationship). The experiment — pods that transport two things between them — goes horribly wrong and starts to transform Brundle into a fly-like man creature. The AIDS connection comes with the depicted disease and bodily deterioration seen in the film.

Horror’s Homophobia Doesn’t Scare Queer People Away

With the queerphobic portrayals in the horror genre over the past 40 years, it’s astounding that queer people have so much fervor for scary movies. Why do gay people love this stuff so much? The fact that gayness was baked into the foundation of horror explains some of the passion. Queer people are able to pick up on so many queer-coded aspects and underlying themes and connect in a way that straight audiences don’t. But even after all the harmful tropes, why keep coming back?

Felker-Martin says her love for the genre has an irresistible “scab-picking element to it” and that it fills a “need to experience intimacy with my own discomfort and terror.” She’s always been into stuff that “scared the sh*t” out of her, she explains, from Jurassic Park’s raptors to Stephen King’s It, which she read when at the same age as the book’s early main characters.

For Owens, what the genre brings to queer fans makes perfect sense. In a fictional world that’s “already off-kilter,” why not? “It’s sort of like, ‘Oh, well, of course, there’s going to be a queer vampire here.’ Because in a world where vampires actually exist, like, it’s not that much of a stretch to say they’re going to be a queer vampire,” says the author. “Because the bigger stretch is actually to say that vampires exist in the first place.”

Not all queer people find themselves fully captivated by horror, though. T’Nia Miller, who played Hannah Grose in The Haunting of Bly Manor, tells INTO that she’s not particularly a fan of horror and unnecessary gore but is intrigued “when done well.”

Of course, someone who she notes does it quite well is Mike Flanagan, creator of Netflix’s “Flanaverse” pieces of horror. Miller will play Victorine in Flanagan’s upcoming series The Fall of the House of Usher, and she says that horror that involves the supernatural is more up her alley. “I believe in the supernatural,” the actor says. “I think we’re foolish to think it’s just us humans that inhabit this space. I think it’s quite egotistic.”

Horror has not been kind to other marginalized communities. Black characters often didn’t have lead roles in the genre, and if they showed up, it was briefly in the beginning and then they were the first to die. While Bly Manor’s Hannah isn’t different in that sense, she’s a main character who tethers the story and has an emotional arc throughout, which evolves into what Miller calls a “gorgeous surprise.”

But the “Black people always die first” trope in horror happens so often that it’s often parodied, and sometimes even acknowledged. Audiences can see this in Scream 2, when Gale Weathers’ (Courtney Cox) new Black cameraman, Joel (Duane Martin), skips town when too many killings start to pile up. And, of course, Scary Movie and its sequel feature joke about Black characters needing to leave because they’ll die first. For Diallo as a director, horror might not be welcoming to her as a Black person, but it’s the essence of the genre that keeps her coming back.

“It can be difficult to analyze, because I think that at its core, what’s appealing to me about horror is emotional,” Diallo says. “But if I think about it, I can also imagine that there’s something very transgressive in the horror genre — more so, I would argue, than a lot of the other narrative genres that we have, because at the core of horror is presenting an audience with something that they find uncomfortable to see … You can really challenge your viewer in that sort of space.”

Diallo is a lifelong fan of the genre but didn’t originally want to create horror films, because it wasn’t “serious enough.” After trying to write scripts that weren’t clicking, she leaned into what she wanted to see on screen, and horror took hold of her and her work. Diallo says that instead of being on the side of the screen where she’d be the character that gets killed first, she’d much rather create art in which she decides that a Black woman gets to be a Final Girl, theorist Carol J. Clover’s term for the trope of the last girl standing to defeat a usually male or male coded sexually aggressive monster.

Last Queer Standing

Despite the complicated and oftentimes unpleasant history of queer people in horror, there have been improvements over recent years. The Fear Street trilogy — co-written by Phil Graziadei, who is gay — not only tosses out stipulations needed to be a Final Girl, who is usually a straightlaced, white virgin, but also features two queer women — one a woman of color — as horror heroes. It doesn’t follow the outdated, harmful rules of Black people dying first (or at all) and queer people not existing, but the three films still perfectly play into iconic scary movie gimmicks and thrills, showing just how unnecessary those old tropes are. There are jumpscares, Big Bads with knives and masks, and a group of teens to pull off a win in the end.

The marketplace is also changing: Gay horror movie creatives who have always been here but couldn’t outwardly put queer context in their projects can now do so explicitly in a market that is more open to those stories. Fuller points to Don Mancini, creator of the Child’s Play franchise, who has incorporated queer themes into subsequent films and a TV spinoff. In Seed of Chucky, Tiffany and Chucky’s adopted child, Glen/Glenda, doesn’t have a gender, and in the new series the title character comes out as gay.Kevin Williamson, also gay, wrote some of the best teen horror in the ’90s, like the Scream franchise and I Know What You Did Last Summer. With the release of Scream (2022), queer characters get a chance to survive in the spotlight, like Jasmin Savoy Brown’s Mindy Meeks-Martin. Fuller says older queer filmmakers are finally getting the creative freedom they didn’t have when they first started telling their stories.

Eleven seasons strong, Ryan Murphy’s anthology television series American Horror Story continues to provide a platform for queer actors. This season, the episode “Something’s Coming” stars a powerhouse lineup that includes Sandra Bernhard, Denis O’Hare, Zachary Quinto, and Isaac Powell. Since his early projects, Murphy has interjected queer narratives and helped spearhead the Emmy Award-winning series Pose.

Angelica Ross captivated audiences with her performance as Candy Johnson-Ferocity on Pose and is making history, once again, with her current star turn in Broadway’s Chicago. The actress has appeared in two AHS seasons and recognizes the importance of trans visibility in the genre.

Related: The 20 Best Trans-Coded Horror Flicks of All Time

“When Ryan broke the news to me that we were ending Candy’s story, he told me right away, ‘You’re going on American Horror Story.’ He was like, ‘I don’t want you to worry — this is not a punitive thing. I just think you’re the one who can carry the story,’ ” Ross told INTO. “I understood the assignment. I understood the implications. And I knew immediately what I would be able to bring.”

But with this influx of new queer horror, there is such a thing as pushing back too hard on negative stereotypes. Owens calls this a “positivist imperative,” or what he notes is a “cold shower of political correctness that has befallen queer media.”

The direct response to harmful horror tropes shouldn’t be to put all gay people in a fully positive light all the time. “Show queer people as backstabbing, as conniving, as manipulating,” Owens says. Part of good representation, after all, is showing that we’re neither evil monsters or perfect victims, but something in between.

Felker-Martin offers a similar opinion, noting that she wants to see “full and complex human beings” in the media she watches and in her own work. This includes “messy, damaged queer people.” It’s just not realistic to have “palatable” or “wholesome” gay people in all the queer roles we see.

Diallo aims to capture nuance in the goodness, or lack thereof, in the characters she writes as well. “I appreciate when my Black characters are ‘bad’ or my queer characters are, because that’s human life,” she says. “I don’t want to make a perfect character. I actually think that robs the characters [their sense of] humanity.”

Fuller notes that with the change we’re already seeing, it will take both new “pioneers” in filmmaking and established ones to tell engaging new stories with queerness at the helm. Miller also says that it’s important to have “any othered” or marginalized person behind the scenes. “Anyone who’s not white, cis … anything that’s not that, those people are part of the creative process. And that’s how it changes,” she says. “Don’t tell our stories. Don’t do that, right? Don’t speak for me. Let me speak for myself.” Miller is a British actor who trained at the Guildford School of Acting and notes that she checked a lot of boxes when it came to portraying typically tokenized characters — lesbian, Black, woman, poor, with two kids — but it’s important not to only “put our faces in front of a camera.”

Still, Owens notes that not all queer people have the same “level of investment” in ethics, so it’s not always the saving grace you might think it is. Even though he has put a lot of queer people in horror on the map, just look at how Murphy has also written queer women as the butt of jokes, such as in the short-lived The New Normal.

Even if homophobia is conquered within the horror genre, the kind of intolerance and judgment around bodies and sexual behaviors is still deeply rooted.

Felker-Martin says that while horror hopefully will continue to move away from transphobic and gay stereotypes and tropes, those aren’t the only harmful ways of othering people in media. “I think horror is going to have a very, very tough, very long battle in coming to grips with the way it’s fed off of and demeaned fatness and fat people for practically its entire lifespan as a genre,” she says, saying that creatives are starting to address it, but “it’s not quite there yet.” Casual fatphobia is rampant in all media and everyday life. Even if homophobia is conquered within the horror genre, the kind of intolerance and judgment around bodies and sexual behaviors is still deeply rooted.

Horror as a whole creates some of the most iconic film references around. Ghostface from Scream can ask, “What’s your favorite scary movie?” a million times and we’ll still love it. The scene of Jack Nicholson sinisterly saying, “Here’s Johnny!” in The Shining is ingrained in our memories. And the image of Michael Myers lumbering toward his victims—knife in hand, with the Halloween theme playing in the background—is so iconic he got a brand new trilogy.

Queer fans don’t just have these memorable moments, they also have the connection to these movies and the relatability to storylines of monsters being shunned. And it’s now kind of comforting to have a somewhat logical explanation behind why we all seem to gravitate toward the spooky or the occult. Yet that doesn’t mean we can’t expect better from a genre that we hold so close.

Queer people often feel abnormal from an early age. But horror media has taught us that “being normal is vastly overrated” and is a haven of sorts, even if many don’t survive until morning.

* * *

Alani Vargas is an entertainment journalist and pop culture enthusiast. She is a contributor for The Daily Beast and Pride.com and has been published on Vogue.com, PopSugar, and Bitch Media; she also recently worked under Netflix’s editorial umbrella. She is a member of GALECA: The Society of LGBTQ Entertainment Critics.

Angelica Ross interview conducted by Juan Michael Porter II.

Help make sure LGBTQ+ stories are being told...

We can't rely on mainstream media to tell our stories. That's why we don't lock our articles behind a paywall. Will you support our mission with a contribution today?

Cancel anytime · Proudly LGBTQ+ owned and operated