It is coursing through our veins, sustaining life and fighting disease, and yet we fear it. The sight of a few drops can make an adult faint. A bucket of it in a movie is the very definition of horror.

Even as Donald Trump contributes his perverted, sexist new layer of blood revulsion (through a history of insults that include journalist Megyn Kelly’s bloody “whatever” and his most recent fabrication about a “bleeding” face lift that cable news anchor Mika Brzezinski never had), make no mistake, people with HIV are quite familiar with the existential threat — and weaponization — of blood.

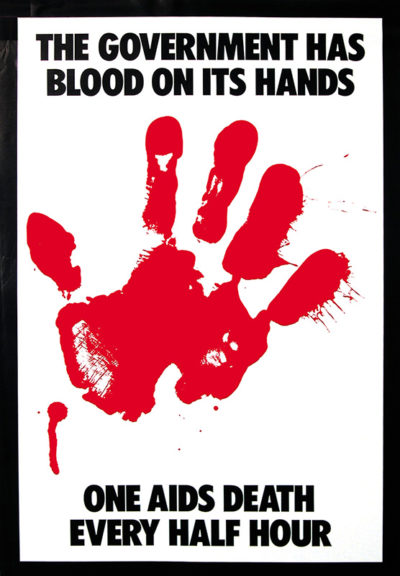

AIDS activists during the early epidemic knew the visceral power of splashing red paint onto their targets or imprinting it onto posters. This tactic wasn’t a second-hand provocation, as if to suggest, say, a blood feud or even bloody consequences. For me, it was a more immediate message that toyed with public fears. “This is our blood,” the red paint symbolized. “Does it scare you? Then fucking do something.”

It’s not as if the public needed any prodding in their fear of blood contagion. As soon we knew how HIV was – and was not – spread, frightened people everywhere fixated nevertheless on fantasy scenarios in which HIV positive blood might somehow come creeping into their bodies. People with AIDS were turned away from public swimming clubs. What if scary-guy-with-AIDS gets a cut and his blood swims over to little Sally?

How about we take this to the next level?

Our newsletter is like a refreshing cocktail (or mocktail) of LGBTQ+ entertainment and pop culture, served up with a side of eye-candy.

When Greg Louganis revealed his HIV status, he was mercilessly badgered to explain why he did not disclose his HIV status when he hit his head on a diving board during competition at the 1988 Olympic Games, drawing those terrifying drops of red. The fact HIV could not survive in any of these situations did not overrule the hysteria.

Artist Barton Lidice Benes literally bottled our uneasiness when he created “Lethal Weapons,” an exhibit in the early 1990’s featuring HIV positive blood captured in small vials and within artwork. The tension it created – the viewer standing inches from biological catastrophe – elevated the work by forcing us to confront something both primal and epidemiologically modern.

Unrealistic fear of HIV blood isn’t limited to the history books. HIV criminalization — people with HIV being charged with crimes based on their HIV status — preys upon outdated fears and public disgust with people living with the virus.

We simply cannot underestimate, then, the historic importance of knowing with certainty that people living with HIV who are on successful treatment and “undetectable” cannot transmit the virus to their sexual partners (being undetectable is a lab marker in which measurable levels of HIV are not detectable in the blood sample). This fact has now been proven, again and again, in a worldwide collection of growing research. The U=U (“undetectable equals untransmittable”) message was created by the Prevention Access Campaign to deliver this very news.

Alas, the fear of blood is thicker than science, particularly when two generations of HIV mortality is concerned. Although a consensus statement on the U=U message has been adopted by hundreds of health organizations in dozens of countries, the message is still being absorbed, often slowly, by a wary audience. And this overabundance of caution extends to the slow-but-increasing uptake of PrEP, the daily pill that renders my virus harmless to people who are HIV negative, regardless of the level of my detectability.

I have been HIV undetectable for the last fifteen years. Paranoid fantasy scenarios aside, my blood is not going to suddenly turn lethal on me — or on you. Knowing this fact has lifted my self-worth in ways that are difficult to describe. I no longer have the nagging feeling, however illogical it might have been, that I was a walking container of hazardous, multiplying cells. My blood is now reduced to the same uneasiness you might have about yours.

The blood inside you might still make you feel queasy. That’s only human. And now, at long last, so am I.

Mark King is Queerty’s health writer

KaiserVonScheiss

Anyone who’s positive should still be required to tell a sexual partner before a sexual encounter. I don’t think is should be a sex offence, where the offender has to register, but it shouldn’t be legal either.

And most people find blood gross. Blood is a biohazard, whether HIV+ or not.

Frank

Yes you should share with someone if you are HIV+; in addition there is the increased HIV panic. Please allow me to explain: you disclose your status to a sexual partner…you both have sex in whatever conditions that you both mutually agree upon. The HIV- person FREAKS out and says that you did not share with them your status.

Therefore if you are randomly meeting men via an app (Grindr, Tinder, Craigslist, etc..) you have your status of HIV+ in your profile as so there is nothing that can occur.

If you meet someone and you hook up I suggest that you once you have stated it send that person a text message or an email with that information something as simple as the word “positive”.

Too many cases are being heard where someone has sex with a HIV+ person and the HIV- person FREAKS out and brings charges. While they might be dropped or go no where it is good to not have to go thru that ordeal.

Heywood Jablowme

You should probably stick with guys who haven’t been tested in 5 years or more and tell you they’re HIV-neg… last time they checked. LOL.

Frank

People lie and it is best to protect yourself in every possible way…

Chris

Over the past few months, I’ve met a couple of men who had no idea what PrEP is. And this was in one of our nation’s largest cities. It seems that we have a long way to go as regards educating ourselves.

ErikO

Sorry you should tell someone you are HIV+ before you have sex, if you don’t do this yes you should be put into jail or prison. It’s illegal to lie about your HIV status in many states and countries.

Given the large number of idiots that believe it’s fine to bareback and have unprotected anal sex as long as they are on PREP/Truvada, and the idiots who believe that they can have all the bareback sex they want and won’t get HIV at all especially not from some guy that’s supposedly undetectable, not to mention the other diseases you can easily get from blood it should be treated as a biohazard.