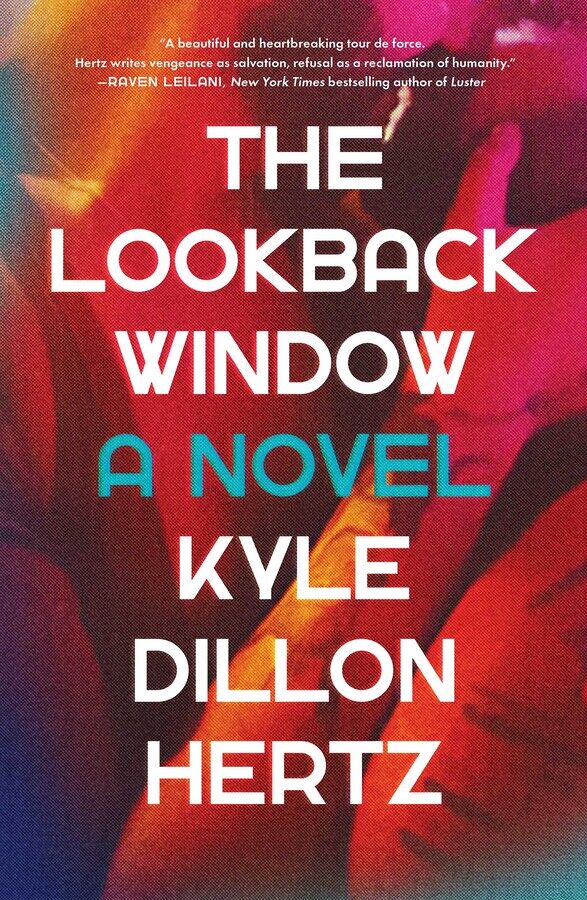

In his debut novel, The Lookback Window—out 8/1 from Simon & Schuster—Brooklyn-based author Kyle Dillon Hertz takes an unflinchingly look at male sexual assault within the queer community.

Hertz tells the story of Dylan, a twenty-something protagonist who survived unimaginable horrors as a child but only now—after the recent passage of New York’s Child Victims Act—realizes he may have an opportunity for retribution.

The “lookback window” refers to the one-year span of time during which former victims of childhood sexual assault are able to seek legal action against their abusers. It’s this real-life legal development thats provides the shape and structure of Hertz’s harrowing novel, which takes place over the course of a single year.

The Lookback Window begs the reader to ask themselves: What is the cost of revenge? What is the right way to deal with anger? And is it more productive to dive into one’s past head-on or steer away from it?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the queer thriller has cultivated a slew of online chatter—before it was even published—making it one of the most pre-ordered LGBTQ+ books of the summer. On book recommendation site Goodreads, users are already debating the book’s difficult subject matter. And on social media, some conservatives have pushed efforts to ban the book for its cover alone: a blurred photograph of two men kissing (a decision made by publishers Simon & Schuster, which Hertz hails as an “awesome choice”).

But the author welcomes the healthy debate around his debut, and is excited about the conversations it’s already starting. Before The Lookback Window hit shelves, Queerty caught up with Hertz to unpack the real-life inspirations behind the novel and the “Viking funeral” feeling of putting such a personal story out into the world. Here’s what he had to say…

QUEERTY: I’d love to start [with] you explaining the genesis for your novel.

KYLE DILLON HERTZ: I definitely knew I wanted to write about men and sexual assault because that had been a big part of my own life, and a big part of the life of the people that I’ve known.

It was kind of an amorphous idea at the time, [when] I was in grad school at NYU. And when New York passed The Child Victims Act, that immediately gave the novel a whole structure—by putting this time limit on it, you have one year to decide whether or not to bring a civil case against your abusers.

At first I was dealing with what that meant in the real world—for me, personally. And then after that, I was like, “Okay, f*ck, this is a novel. If you’re going to write a novel, you need a structure. And once you have that structure, you can fly through it.” So the book ended up being written relatively quickly—probably in less than a year, honestly—because that structure just gave me the perfect shape.

What made you want to write about this subject [male sexual assault] specifically?

It was moreso just a natural extension of conversations that I’ve already had with people that I had met. Sexual assault of both men and women happens at nearly the same rate, but male-on-male assault is vastly underreported. One of the reasons why there’s that disparity is because it’s systemic—the FBI didn’t even include rape as a possibility between two males until 2012—so the definition has only recently changed. And before then, there are no statistics; because according to the government, it [male-on-male assault] didn’t exist.

Utilizing anger as a tool is obviously a theme that runs throughout the novel, [as well as] this idea of confronting truth.

I think that’s a huge part of it. Because, of course, when you are trying to recover from violent trauma from violence, sexual trauma—from anything—you really learn how much shame conditions you to secrecy. Whether it’s: you’re threatened so you can’t tell anyone, whether you don’t think people believe you, whether you think it will impact people’s perception of you—which is also, perhaps, a byproduct of the male sexual assault culture: the idea the men should not be seen as weak. And so they don’t talk about it.

I feel like there’s a prevalent narrative in our culture of “the perfect victim.” The perfect victim is supposed to not want sex after an assault. I knew from my own experience that that wasn’t real. It was important for me, in writing this novel, for there to be a lot of consensual sex in the book and for it to be pretty explicit. Of course, it happens that some victims never have sex again—but for a lot of people, you do still want sex, especially queer men, where sex is a huge part of our culture. And I needed to have a book that frankly [said,] “Yes, this horrible thing happened sexually to Dylan. But also he’s still f*cking, he’s still horny. He’s still wanting to connect.”

There’s also the question of what to do with vengeance. Obviously, that’s very timely because so many people are asking, “What do I do with my anger?” That question—of “how do we allow anger to manifest in our lives?”—was that a question you had while writing the book?

There are just no clear answers. I think every person deserves to figure out what they want and how they can live with themselves. To me, that looks like holding people accountable in whatever way that means. That means telling the truth. That means letting other people know what happened. That means letting the people who did these things [are] held accountable, despite the systemic failures and the systemic inadequacies.

I wish more people got that chance. I wish everyone on Earth got a “lookback window,” where they had a year to just think like, “F*ck, what do I wish I could be angry about?” I think a lot of people would live healthier lives if they were allowed to be angry, if they were allowed to seek accountability and justice for these things that wrought with us, right?

How does it feel to finally put this book out?

The writing of the book was, deeply, one of the most emotionally fulfilling experiences of my life. Taking something and transforming it into something different felt like passing it on in some ways—like those Viking funerals where they put a dead body in a boat and set it on fire for everyone to see. That’s a little bit of the experience of this novel being out there.

I have heard from some people who the book has affected—and it’s honestly not just queer men. [It’s] a lot of people who I think just want to be angry but don’t feel that they can, or they want to be messy, or they want to talk about things that we don’t have the language for. When you’re actually in it—when you’re in grief, when you’re in trauma—none of that f*cking matters. Like, you need the messy experience. And I think allow[ing] people that in the form of a book—even [for] a moment—is worth it.

I’m sure it’s quite daunting to now have people talk about it and pick it apart at the same time.

I’ve been lucky in that there have really been mostly good reviews. But there have been people who—I don’t even know if they read the book—found out about the book and were just posting reviews everywhere, like, “This book is about homosexuality; it’s disgusting.”

And things like that, to me, are the shocking part. It’s not that I forgot what homophobia is, but I don’t allow it in my life. So, for it to enter in this manner has been shocking, because I’m like, “D*mn, these f*cking piece-of-sh*t prejudiced people are out there and on the hunt!” And I mean, again, with everything going on in the world—with queer people, with queer books—knowing my book, [just] because there are two men making out on the cover, it’s just gonna be banned off that? That’s the crazy part to me. What’s crazier than any negative review is that simply two men kissing is enough for someone to seek me out and come after the book online.

And there’s been some debate about the content in your book, right?

I feel like if you’re writing about something horrible then it should be explicit. If you’re reading about war, rape, homophobia, misogyny—these things shouldn’t make you feel good. If you’re reading a book that has these themes in it and you’re thinking, “Oh, I feel comfort, it’s not that scary,” the writer did a bad job. I say: let things be fucking explicit. And, if you’re uncomfortable with it, good. That’s exactly what you should be. These things aren’t fun, right?

The Lookback Window is on shelves now, and is available to order via Simon & Schuster.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.

Dangbad

Always thrilled to see more substantial articles on Queerty.

Also, just preordered the book on Kindle.

Chi_Chi_Man

Happy that this topic is finally getting attention, but the author’s statement that “Sexual assault of both men and women happens at nearly the same rate” is wildly inaccurate and irresponsible.