The following is an excerpt from Weirdly Queer: Exploring the LGBTQ Perspective of the Paranormal, Occult, and Mysterious World by paranormal expert Ken Summers available online and at all good bookstores.

One year after losing his virginity on a picnic in the woods with a handsome young man, Noel Coward was on stage in his second performance of Where the Rainbow Ends. His mother Violet questioned her encouragement of her son in acting while he was questioning his own sexuality.

At this time in early 1913, fate intervened when she learned of a public mind-reading act being performed by Miss Anna Eva Fay—famed medium and mentalist from Trumbull County, Ohio—at London’s Coliseum. Audience members were given small sheets of paper to write down any questions for her, though she could only promise the time to answer a few of them. Miss Fay stood on stage, pulled out a random paper and read it.

“Do you advise me to keep my son Noel Coward on stage? – Violet Coward”

She turned to Coward’s mother who stood in the crowded theater. “You ask me about your son Noel Coward. Keep him where he is, keep him where he is. He has a great talent and will have a wonderful career!”

And with that prediction, one of the few she gave that evening, Miss Fay fainted and was carried off stage. (Spectators had been warned in advance the medium was “easily fatigued.”)

Her advice was wise, regardless of its source; Coward went on as an actor and playwright of great importance in England. One such play, inspired by séance mediums of the same ilk as Miss Fay, eventually became a film in 1941 under its original name, Blithe Spirit, which had also drawn inspiration from other paranormal incidents in his life.

But the heyday of simple mediumship was already starting to wane. Audiences wanted more thrills to match the technological leaps happening all around them.

As the 20th Century appeared on the horizon, while spiritualism maintained its audience with the public and continued to flourish, a more scientific interest in the paranormal arose. Psychoanalysis was gaining widespread appeal; matters of the mind and soul were pulling away from religion and entering scientific laboratories and thorough research templates.

Technology advanced from the Industrial Age of the mid-1800s into the turn of the new century while mediums and their spirits kept pace with new advancements. Each new technological creation meant a new source of evidence for paranormal phenomena.

“[T]he tapping specters of spiritualist séances…appeared quite promptly at the moment of the invention of the Morse alphabet in 1837. Promptly, photographic plates—even and especially with the camera shutter closed—provided images of ghosts or specters which in their black and white fuzziness, only emphasized the moments of resemblance. Finally, one of the ten uses Edison predicted…for the recently-invented phonograph was to preserve the ‘last words of the dying.’”

At Cambridge’s Trinity College during the 1870s, a small group of friends—Frederic W.H. Myers, his physician brother Arthur, physicist William F. Barrett, Henry Sidgwick, and his wife Eleanor—would gather to discuss and investigate ghosts and mediums with increasingly scientific scrutiny. That social club eventually coalesced into what became the Society of Psychical Research (SPR) in 1882.

Those early founders were quickly joined by friends and other interested parties including Edmund Gurney, George Balfour, Frank Podmore, and scientists William Crookes and Sir Oliver Lodge.

Not surprisingly, several of these men and other early members were either known or suspected homosexuals. While the young Society was finding its footing, inner controversies and accusations made for a rocky foundation.

Arthur Sidgwick, Eleanor’s brother-in-law, was friends with one of the first SPR members, author John Addington Symonds, a “practicing and proselytizing homosexual,” whose friendship contained heavy homoerotic overtones; later, a love interest with a Rugby boy created an “external danger” for Sidgwick.

F.W.H. Myers “suffered the same sexual problems as Symonds in early adulthood” but apparently outgrew his same-sex desires becoming a ravenous, unabashed womanizer (which could be argued to be an act of overcompensation in some respect).

Related:

This Victorian scholar was way ahead of his time on gay issues, but he treated his boyfriends like dirt

In the late nineteenth century, John Addington Symonds fought back against his colleagues’ refusal to acknowledge historical same-sex relationships.

SPR’s first Vice President, Roden B.W. Noel, had a “handsome, feminine manner, and was inordinately vain.” (He engaged in trysts with Symonds frequently.) H. Graham Dakyns, another of Symonds’ friends and early member, became involved in a sexual relationship with one of his pupils at Clifton College: Cecil Boyle. Oscar Browning was dismissed from his position as master at Eton after allegations surfaces accusing him of becoming intimately involved with some of the boys.

A string of suicides connected to SPR all were alleged to have been (at least partially) the result of deviant sexuality and fears of public embarrassment.

When housekeeping staff failed to stir the guest in a room at the Royal Albion Hotel in Brighton, England, on Saturday, June 23, 1888, the manager broke into the room around two o’clock in the afternoon. Forty-one-year-old Edmund Gurney lay on his left side on the bed, a sponge-bag containing an unknown liquid—possibly chloroform—covered his face. A letter addressed to Dr. Arthur Myers was found in his pocket.

The physician and close personal friend spoke at the inquest. To avoid the scandal of suicide, Dr. Myers’ testimony claimed Guerney died of an accidental overdose of pain-killing chloroform (used, according to the doctor, to relieve his suffering from epilepsy and Bright’s Disease, though no mention of such ailments were found in his medical record prior to his death), leading to the formal conclusion of accidental death without an autopsy taking place.

Gurney had suffered manic episodes of depression while at Trinity and his work had suffered from its effects, but these mental problems were never addressed.

Trevor Hall examined the incident in his book, “The Strange Case of Edmund Gurney”, with all the diligent deductions and twists and turns of a whodunit mystery, alleging that the true motivation behind his death was becoming aware of certain revelations of fraud involved in the research and writings he’d devoted several years of his life to documenting, genuinely believing them to be true.

(Some sinister activity on the part of the Myers brothers was also hinted at, but entirely through speculation.)

It had been too much for him to bear, leading to his discreet stay at an unfamiliar hotel in the city he had spent countless months conducting methodical investigations and the quiet taking of his own life.

Hall’s reasoning that fraud had been the sole instigator and that later rumors of homosexual liaisons were unfounded hedged on the facts that; A.) there was no conclusive evidence of any sexual infidelities; and B.) Gurney was very happily married to his wife, Kate Sara Sibley.

The couple had a daughter who later alleged that F.W.H. Myers had tried to prevent her parents from marrying and went so far as to invite himself along on their honeymoon. This strangely intimate friendship aside, one need only look at Oscar Wilde’s happy home life, marriage, and children to see that these factors have no bearing on sexuality (particularly in the case of bisexuality).

What ultimately led to the rumored homosexuality was the extensive work on hypnotism and thought transference (known today as extra-sensory perception, or ESP for short) conducted over the final several years of his life in Brighton.

Gurney and Frederic Myers had originally gone to Brighton in 1882 to examine the claims of 18-year-old George Albert Smith, detailed in several articles of the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research in 1883. It was Smith who introduced Gurney and SPR to the ‘Brighton boys,’ a “surprisingly large circle of young [working class] male acquaintances” aged 12-20 years ranging from a baker’s son to an intelligent young mechanic.

ESP experiments were conducted on at least nine young men by Gurney—with occasional assistance from brothers Frederic and Arthur Myers and fellow SPR member Frank Podmore—and Smith was immediately hired as Gurney’s personal secretary.

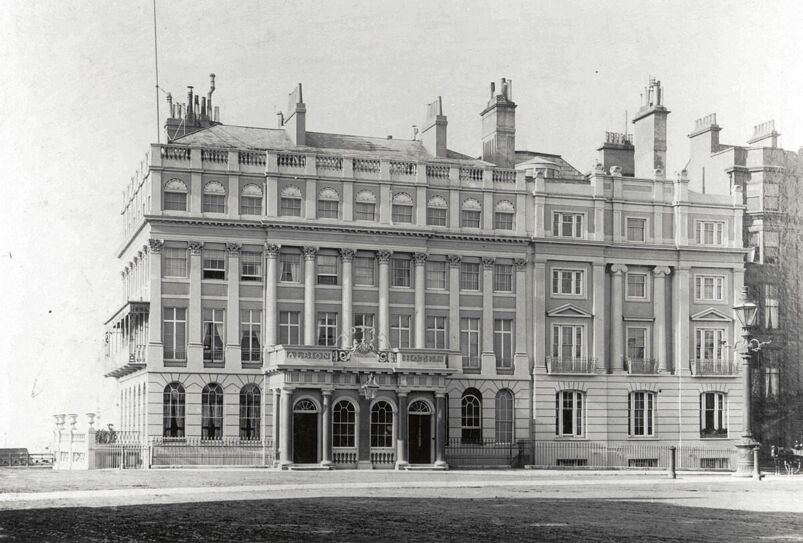

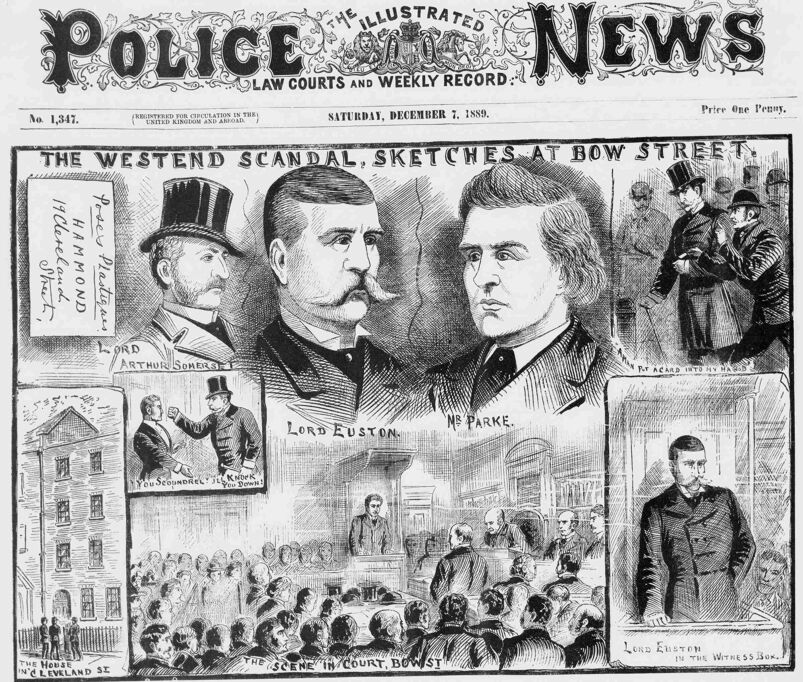

One of the boys, a telegraph clerk of 19, featured prominently in experiments recounted in “The Proceedings of the Society for Psychic Research, Volume V.” His age and employment were quite significant: in 1889, while the Brighton experiments were still ongoing, a male brothel located at 19 Cleveland Street, London, was raided by police; five of the male prostitutes were “telegraph boys” (as telegram delivery messengers were often called) hired on by the Post Office.

Henry Horace Newlove, a clerk in the Accountant General’s Department, had introduced them to brothel work and would serve a prison sentence of nine months for “assisting in keeping a disorderly house.” What came to be known as the Cleveland Street Scandal (or Affair) would go on to connect Wilde and many prominent British officials to male prostitutes culminating in the infamous trials which sentenced the playwright to hard labor in Reading Gaol.

In one peculiar reference, Sir Oliver Lodge wrote to SPR Council member J.G. Piddington in 1908, making a reference to “the street boys” and Smith; “street” being added later in the margin, possibly in similar reference to the “boys of the Boulevard” in Paris, meaning youths acting as male hustlers.

While the exact circumstances and reasoning is unclear, Arthur Myers himself died of a similar narcotic overdose just five years after Gurney. Yet there was one member of SPR who not only had involvement with the “Brighton boys” but also personal postal connections: Frank Podmore.

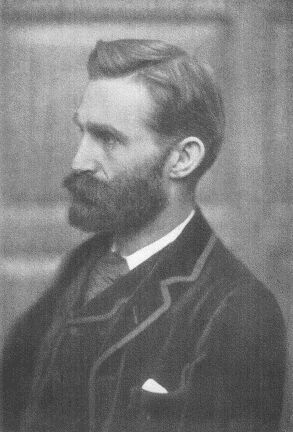

At the time of his involvement with SPR, Podmore was a senior clerk in the Secretary General’s Department of the Post Office, headquartered at St. Martins-le-Grand, London. He was a prolific writer, responsible for a two-volume collection of known mediums’ biographies and studies, “Modern Spiritualism,” as well as countless Journal articles and works on a range of paranormal topics.

Initially pulled into psychical research while attending Pembroke College and quite positive about the research being conducted, Podmore grew skeptical on matters related to the otherworldly in the 1890s.

His less-than-flattering bluntness regarding fraud and dubious doubts of evidence being readily accepted by many other researchers in the field earned him a reputation as a difficult person. SPR’s hardened skeptic did soften his views a bit in the early 20th Century, finding some of the emerging evidence better able to hold up to scrutiny.

Podmore theorized that telepathy was but one of several “long lost but once serviceable faculties” used consciously by early humans which had faded into a residual remnant lost in the subconscious. (PSPR) He also proposed that telepathic projections at the moment of death could be responsible for what he referred to as “crisis apparitions.” Even during his most skeptical periods, his belief in telepathy never wavered.

When not engaging in paranormal research and writing or curating the ancient erotica collection at the British Museum, Eric Dingwall’s favorite pastime was gossip—particularly if it related to members of SPR.

In 1954, he met with George A. Smith, then 90 years old, and when the topic of sexuality came up with regards to the Brighton experiments and any known intimacies with relation to himself or Gurney and the young men, Smith responded in the negative, adding that the Brighton boys were “Mr. Podmore’s young men.”

Behind the curtains at Dean’s Yard, Westminster, the private life of Frank Podmore was more peculiar and mysterious than any psychical manifestation. In 1891, he married Eleanore Bramwell, with whom he had no children. Eleanore was an attractive, intelligent woman, yet the marriage was a tumultuous one.

Writer and friend Ernest Rhys recalled a curious conversation with her once while visiting; finding her alone, Rhys inquired as to the whereabouts of her husband. With a laugh hinting at some secret knowledge on her part, she said, “He’s gone to the post office to play cards.”

Weirdly Queer: Exploring the LGBTQ Perspective of the Paranormal, Occult, and Mysterious World by paranormal expert Ken Summers is out now.

Related:

Do ghosts believe in themselves? Here’s what one queer paranormal investigator has to say about it…

The following is an excerpt from “Goodbye Hello: Processing Grief and Understanding Death through the Paranormal” by Adam Berry available through Regalo Press on September 26, 2023.

This article includes links that may result in a small affiliate share for purchased products, which helps support independent LGBTQ+ media.

Pietro D

Complete Bull Shit!