Being gay wasn’t easy in the ’70s — there were the ripples of Stonewall and Harvey Milk, not to mention the American Psychiatric Association had just declared that homosexuality was not a mental illness.

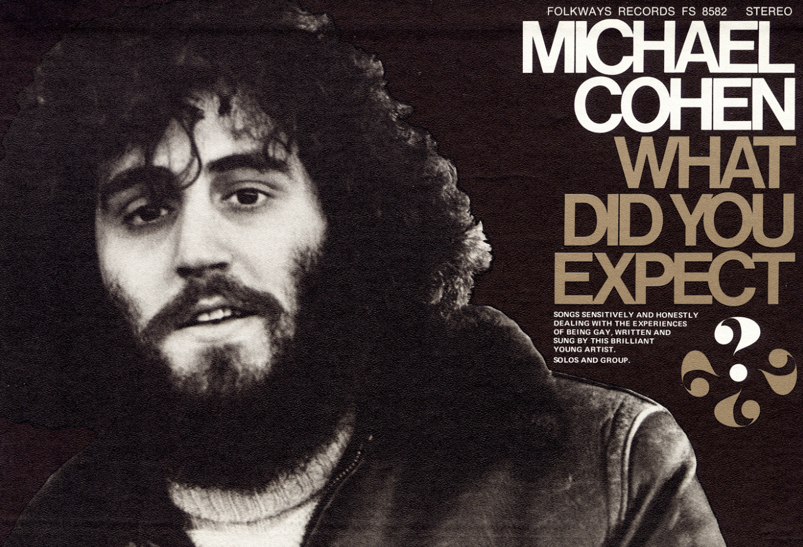

It’s no wonder folk singer Michael Cohen chose “The Last Angry Young Man” to open his 1973 debut album What Do You Expect?, billed as “songs sensitively and honestly dealing with the experiences of being gay.”

The New York musician and cab driver (not to be confused with *ahem* the other Michael Cohen) is often overlooked as a queer music pioneer, but his unpolished candor and musings on love, loss, and identity gave a voice to a pre-Walkman generation of gays searching for connection on airwaves.

And there’s a reason why What Do You Expect? continues to strike a chord. If you don’t see it in Cohen’s stare from the cover, you’ll hear it in his Bob Dylan-esque vocals, somber piano chords, and guitar licks.

Unlike his folksy contemporaries, Cohen bore the weight of being gay in the ’70s on his shoulders, a burden he begins to unload from the opening lyrics, a nod to teenage years in conversion therapy:

“My mother said, the day I came out to her / She said, ‘You don’t want to be the last angry young man,’ / And I said ‘I don’t know, got so much inside of me that ain’t ever come out.’”

Because of this, a palpable sense of melancholy underlies the seminal album’s entirety. Still, the album’s crushing moments are amongst its most revolutionary.

Nearly 50 years before “Sad Girl Autumn” would enter the indie lexicon, Cohen was gazing at fallen leaves on “Gone,” remembering a newly out-friend who died. And while today’s LGBTQ+ pop singers are lauded for lyrics with same-sex pronouns, Cohen never minced words in 1973, name dropping exes like Frederick, Jonathan, and Peterson on “Bitterfeast,” whilst imagining a future lover to “nestle in his fur / And never be to blame.”

However, Bobby doesn’t get off as easily in “Pray to Your God,” a swinging kiss off of a ditty. Amidst promiscuity and substance abuse, Cohen invites him to:

“Go off to Cape Cod / Pray to your God / Stick in the needle / Until you find the vein.”

We’ve always been petty!

Bobby is also mentioned in pensive standout “Orion.” Its zinger-of-a-refrain (“Now you’re on your crusade / Me, I’m a gay blade / And we’ll get together somehow”) would’ve surely appeared in countless Grindr bios, had the app — and smart phones — been around.

Perhaps Cohen was ahead of his time.

Hyper specificity is key for today’s biggest musicians — from Taylor to Troye — but not everyone was on board with What Do You Expect?’s frankness. In 1974, The Advocate’s Christopher Stone called the record “self indulgence at its ego-masturbating worst,” writing that Cohen “[composed] songs the way some people write diary entries” and not every thought “must be waxed for posterity and peddled to the public.” Everyone’s a critic!

It’s ironic that What Do You Expect? is most remarkable for its diaristic observations, as Cohen’s words serve as a time capsule of life as a young gay man trying to find himself in the height of the gay rights movement.

Cohen would go on to release one more album through Folkways Records, applying a higher level of stereophonic varnish to his morose musings for 1976’s Some of Us Had to Live. Both LPs are on streaming via the Smithsonian Institute, a partnership the singer-songwriter’s anti-capitalist spirit may have hated.

What happened next?

Perhaps the business was too rough for a tender soul who hand wrote liner notes and penned lyrics like “You’d have loved me if you only knew how.” Cohen largely disappeared after his sophomore effort, reportedly venturing into the porno business as a producer until he passed away after a 10-year battle with AIDS in November 1997.

Revisiting the record, it’s hard not to feel sad for the singer-songwriter, who, over hopeful harmonicas on “Bitter Beginnings,” dreamed his lover would “come into my bed / And he’ll kiss my forehead / And I’ll know that my life is worth living.”

Still, Cohen would likely feel peace in knowing his words continue to touch generations of gay men looking for direction.

“If when I was fourteen or fifteen, I could have heard someone I respect, who was gay, sing love songs, hate songs, anything –– it would have meant something,” he told InTouch in 1974. “I was into Dylan. If there’d been someone like that — who was gay — it would really have made a difference.”

abfab

MUSIC

Review: Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man, Original Soundtrack

Selecting a singular moment is difficult, since I’m Your Man is packed with one show-stopping performance after another.

by Preston Jones

August 3, 2006

Leonard Cohen has shaped generations with his haunting compositions and biting lyrics, and his influence still echoes today, with performers as diverse as Nick Cave and Antony Hegarty (both of whom appear here) delivering a brand of powerful, idiosyncratic music with its roots in Cohen’s unique worldview.

Recorded live in 2005 at the “Came So Far for Beauty: An Evening of Leonard Cohen Songs” at Australia’s Brighton Dome and Sydney Opera House

Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man also serves as the soundtrack for Lian Lunson’s acclaimed documentary. Each musician is well-suited to their song of choice: the Wainwright clan (Rufus and sister Martha) deliver stunning renditions of such Cohen classics as “Tower of Song,” “Chelsea Hotel No. 2,” and “Winter Lady,”

(Anthony Hegarty) ANOHNI renders “If It Be Your Will” as a mesmerizing, upbeat funeral march.

Built like a killer mixtape, the I’m Your Man soundtrack segues seamlessly into various moods; the Latin-tinged “Everybody Knows” contrasts neatly with Cave’s reading of “I’m Your Man,” and Teddy Thompson’s heartbreaking “Tonight Will Be Fine” rests nicely against Beth Orton’s poignant interpretation of “Sisters of Mercy.” As indispensable a document as the film of the same name, I’m Your Man is a fascinating tribute to one of popular music’s most influential troubadours.

kevins48

huh?

Eddiedol

Wait….what?? Dating myself here but that comment reads like the set-up to an old Emily Litella skit…

still_onthemark

“abfab” is versatile… he’s a floor wax AND a dessert topping!

abfab

Never mind. LOL

I saw Leornard Cohen immediatley and got all excited. Do try to watch the Concert Documentary. It’s where I discoverd Antony And The Johnsons. OMG….they are incredible!.

Love,

Lemon Pledge and Cool Whip and Emily.

Diplomat

Never heard of him

still_onthemark

I’m surprised I never heard of him before now. When I came out my older friends all seemed to have the Jobriath album which was also from the early ’70s (Queerty has written about Jobriath before) but maybe Michael Cohen was someone they hadn’t heard about? Great lyrics!

Bosch

I spent stupid money on getting this CD a few years ago, but I’m glad I have it. Seems like it’s impossible to find now.