Barry Sandler has made his share of cinema history. The writer of hits like Kansas City Bomber and The Mirror Crack’d, he made headlines in 1982, penning Hollywood’s first ever queer mainstream film, Making Love. He also became one of the first celebrities to come out publicly during the promotion.

I know Barry myself. A longtime writing professor at the University of Central Florida’s film school, he instructed me in screenwriting and the fine points of cinema.

This year, Barry celebrates a personal milestone, Making Love’s 35th anniversary, with special screenings around the country. With the torrent of LGBTQ content and LGBTQ-friendly content now easily available everywhere from networks to local cinemas to streaming services, it’s hard to imagine a time in which we were all but excluded from the entertainment industry.

I caught up with Barry after a screening in Los Angeles for a candid chat about the film, his career and how far we have come in depictions of queer life.

How about we take this to the next level?

Our newsletter is like a refreshing cocktail (or mocktail) of LGBTQ+ entertainment and pop culture, served up with a side of eye-candy.

It’s the 35th anniversary of Making Love.

It’s a whole different world now. I think a lot of that has to do with television. And it’s great, because television for the past 10 or 15 years has been great about showing gay people. And when you see so many gay characters, it really de-stigmatizes it. A lot of the bigotry comes from ignorance—that perception that was promoted by the movies for so many years that make gay people out to be freaks. And people who see those images make gay people out to be freaks, to be scorned.

I remember once you said it was Pauline Kael who sparked this idea in you, the idea of something personal.

Well she had written a review of an early film I did, when I was just out of film school that really slammed me for having a film school sensibility. In other words, for creating characters and conflict, really, more out of the realm of other movies than real life. That affected me very deeply because I really admired her writing. And that was sort of a turning point for me in terms of where I wanted to go as a writer, and really compelled me to dig deeper into my own personal issues. So finally, Making Love, at the instigation of Scott Berg [A. Scott Berg, the Pulitzer Prize winning author who wrote the story] who I was involved with at the time, really pushed me to dig deeper into my own personal issues, and ultimately write a coming out story. Although I had been out, I wasn’t publicly, and I resisted the idea. There’d never been a positive gay themed film. There’d never been a film before that showed gay men or women in a positive light. Listen, we get so much of our self perceptions from movies and TV.

Of course.

And when you’re wrestling with your sexuality and you feel these impulses for people of the same sex, and society keeps telling you it’s wrong. You grow up believing that. And it’s totally reinforced by the movies, at the time, growing up in the 50s and 60s and even the 70s. So the idea that really intrigued me about Making Love, while at the same time I was a little bit scared about exposing so much of my own self. At the same time I was intrigued and fascinated by the idea of writing a movie that would present a gay person in a positive light.

So that idea really, ultimately helped me overcome any fear I had of self exposure in writing the film.

Now how many movies had you done at that point, had you written?

I had done The Loners, Kansas City Bomber, Gable & Lombard, The Dutchess and the Dirtwater Fox, The Mirror Crack’d. These were all big, glossy Hollywood movies with big stars. These were comedies, love stories, romances; they were not really personal stories. I mean, they were personal within the characters themselves, but they didn’t draw upon my own life.

But that’s a good career going on, spread out over five to ten years, big movies, hopefully with big Hollywood paychecks going with it, and all the glamour of the time. How did you meet Scott in the midst of all this?

Scott’s brother Jeff was my agent. Jeff Berg, at ICM. I met Scott in the office one day, and we just started talking, and went down the elevator together, and when I got to my car we ended up talking. And we ended up talking for like 3 hours.

Oh wow.

And we formed a connection. And that lead to making love, and to Making Love.

Well that’s good. It’s always fascinating to see the art in the context of the artist. So how long were you guys together?

Well that element lasted not that long. But we remained close beyond that.

So were you still together when you wrote the film?

By that point we were still very good friends.

And you still remain good friends?

Oh yeah. We keep in contact all the time.

So then how much of Making Love is based on your relationship, or is it autobiographical?

Yes and no. Certainly, and you know this as a writer, you draw upon your personal experience, and with this more than anything I’d done. So yes, I drew upon my own life experience for both characters really. So while it wasn’t really autobiographical, it certainly was informed and shaped by my own life experience.

Do you feel like it’s still the most personal thing you’ve ever done?

Oh yeah. Absolutely. Sure it is. But even Crimes of Passion, which I did afterwards, still drew upon my own dealings with intimacy and relationships and those elements, perhaps even more deeply, but certainly as much.

Those two have always struck me as interesting companion pieces, and the older I get, it’s also interesting to me that those both have huge gay followings. Making Love obviously, for obvious reasons, but then Crimes of Passion, it was sort of counterintuitive.

It does have an enormous gay following. And we’ve certainly had anniversary screenings over the years. We had a couple years ago for the 30th anniversary, Outfest did a showing. The Montréal Film Festival did a showing that I went up for. The Spectacle Cinema in Brooklyn had a month long tribute to the film. So you’re right, the film has endured and it has a huge gay cult following. I get emails all the time from people who love the film. It’s wonderful.

That’s still so strange to me, but it’s wonderful at the same time.

I’ll tell you this: the year it came out, for Halloween on Santa Monica Blvd. there were a lot of people dressed as China Blue. Which was very gratifying for me to see.

So what was the process from the time you and Scott started the script for Making Love, what was the process like? How long did it take you to—?

Well here’s the deal. I knew because there’d never been a film that dared to show gay people in a positive light before, I knew it would probably be a very tough sell. So I told Scott, I’d do it if we knew in advance that a studio would be interested in the subject. And he was very close with a woman who was head of development at Fox named Claire Townsend. Sherry Lansing was the head of production at Fox. Scott went to Claire and told her about Making Love, and she went to Sherry and told her, and Sherry said yes, let’s develop this movie. So once I knew that if the script turned out well they’d be willing to make the film—and it took two women, by the way, to make that happen. I don’t know if any men, straight or gay, at the time would have even dared to develop this. They gave it to Dan Melnick who’d just a development deal as a producer. He was a very successful, prestigious, distinguished producer at the time who had produced Altered States for Ken Russell, All that Jazz for Bob Fosse. So he came with credentials. He read the script and called me at one o’clock in the morning to tell me he’d never been so moved, and he wanted this to be his first movie at Fox. So once Sherry and Claire developed the film, and Melnick said he would produce it, that’s how it got made.

So then, Arthur Hiller who had done Love Story prior to that, very successful commercial director, he signs on to do it. The casting was a process to say the least.

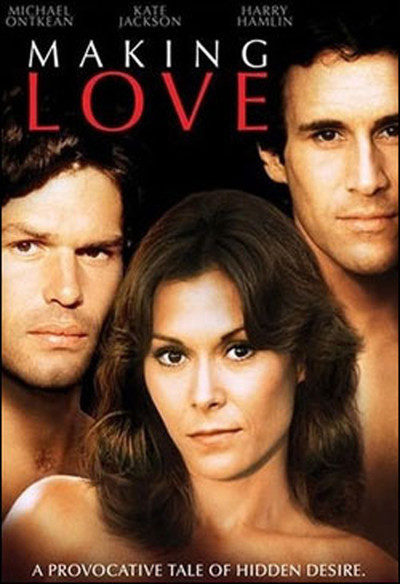

No big star at that point had the courage to play that part, to play gay, to kiss another man on the screen. This was the Reagan era. So rather than wait for weeks to try and get a star, Dan and Arthur and Sherry were savvy enough, and prescient enough to just make the movie. They did feel that they wanted a name for Claire, and that it was important to get. And Kate Jackson was a huge television star from Charlie’s Angeles, and she very much wanted to do the film. So we decided let’s just go with two very good actors. And both Harry [Hamlin] and Michael [Ontkean] were very up and coming. Harry had just done Clash of the Titans, and a couple of other movies and was just on the verge. And to his credit, and god bless him for it, a straight actor on the verge of breaking out, had the balls to say yes, I want to do this movie. It’s important. And Michael, the same thing. So we ended up going with the two best actors rather than two movie stars.

So while all this was going on, you were not out publicly, because indeed, nobody was publicly out.

Nobody talked about it. But when the movie came out I thought it was imperative, and incumbent upon me to give the film some credibility. And people said I was crazy, that it would kill my career. You know, in 1982, Reagan era, they were telling me it was a dangerous thing to do. And I thought, not only is it important for me to give the film legitimacy, but it was important for people to see not only that a gay man could have no problem coming out, that I had nothing to fear, nothing to be ashamed of. But also I was sort of counter to the image of the big, flamboyant queen. I thought it was important to go before the public to, in a way, counter that image, but also to show that I had no fear about admitting that I was gay. I thought maybe gay people out there, seeing that, would have less fear about owning their identity to themselves, and that straight people could maybe, somehow reassess their perceptions of what gay people were.

How’d the movie do when it came out?

So the film opened in selected cities, and the first week broke records. I mean, in San Francisco, New York, Houston, in the major cities it did extremely well that first week. Once it expanded into Kansas and Oklahoma and all that–not so well. But interestingly, in Salt Lake City—Mormon town—we noticed that the biggest selling shows in the theatre where it played in Salt Lake were the 12-noon show. Meaning, guys would go off on their lunch hour—a lot of married guys—would go see this movie. And it took a huge spike at 12 o’clock. And they were curious. Fox said, why is that? And the theatre owners said they had a lot of men coming in with wedding rings on.

That is very interesting. What kind of impact did it have on your career?

Well, listen. The following year I sold my script for Crimes of Passion for a lot of money. Now, I’m sure there were people who didn’t offer me certain projects once I acknowledged that I was gay. But you know, who gives a shit? I was also somebody who was more concerned with writing, at that point after Making Love, with writing movies that I felt were important. So I was always kind of a spec writer anyway. But if you write a script that people want, they don’t care if you fuck sheep.

What was it like to be gay in the 70s, sort of before things turned bad with Reagan and AIDS?

Well, being gay in the 70s, pre-AIDS was terrific. It was great. Sex, drugs rock & roll. It was bars, parties, sex on every corner, everywhere you looked. Now, the sad thing is a lot of people paid a price for that too. I was very lucky that I didn’t, but a lot of friends of mine did. And the 80s was the counter to that. Friends died every week. Going to funerals, seeing people fading away before my eyes—good friends. I have an address book that I every now and then will go through, and every page there are two or three names of people who are gone, who never got to live their lives.

That’s something I always wonder about. I can’t imagine what it was like to see the party of the 70s give way to the eulogy of the 80s.

It was brutal. It was just heart-wrenching. You’d get a call from somebody and they’d tell you that somebody was sick. Somebody that you knew, that’d you’d been with. One of the most relieving days of my life was when I got my HIV test back and it was negative. I was one of the fortunate ones. There were way too many that weren’t. And [long pause] I miss those people. Those were my friends. In it’s own way, it was a Holocaust because we lost a lot of lives. And many people think it could have been, not averted, but curtailed, if the government under Reagan had acted to put money into finding cures instead of tax cuts for millionaires, and getting drugs certified. There were other things the government could have done that would have saved a lot of lives.

When you look at the gay community now, I think, Making Love is a movie way ahead of it’s time. There’s something—not naïve, but there’s a certain purity to it. The idea that two people can love each other, and make love with each other and not worry about dying. There was no way I could conceive of that until a few years ago, before things like PrEP.

In the two years gay marriage has been legal [nation wide], the world hasn’t come to an end, which is what religions fundamentalists always said would happen. Gay people just go about their lives, and nothing bad happens. So why not just accept it?

With everything you’ve seen, and with everything you’ve lived through, do you ever think about writing a sequel to Making Love?

It’s so funny, at a Q&A on Saturday, one of the people in the audience asked, ‘what do you think happened to Bart after the movie?’ And I said Bart’s story ended with the movie. Harry said that maybe because [Bart] was promiscuous, maybe he contracted HIV. Maybe he went on to success as a writer. It’s an interesting idea to do a sequel. I’d have to think about it.

With everything you’ve seen, where do we go from here as a people? As a community, what is our charge to our country, to our community, to our world?

The only positive effect of the HIV crisis was that it woke up the community. It energized the community. It mobilized the community. It brought us closer together, it bonded us, it made us stand up for our rights. It made us fight for our rights, demand our rights. It made us more impassioned about our right to be who we are, and not to be condemned for it. It’s tragic that that’s what it took but at least that came of it.

Orson Welles used to say when you die, no matter how old or young you are, there should be that one thing that when God says to you, “Why should I let you in here?” You can say, “because I did this as an artist.” Is Making Love that for you?

I’d say so, if only for the effect it had on peoples lives. Certainly politically, sociologically, culturally, not only for its place in film history, but for the way it affected people’s lives. There’s no question. That’s pretty profound.

Making Love is available on DVD from Fox Home Entertainment.

avesraggiana

The sad thing is, that after this movie was released, the two male stars never saw their names on the big screen again. Only TV, in the case of Harry Hamlin. They were blackballed alright, for being so daring as to take on those gay roles.

Rusty66

I had also heard that …

Edwin Baca

I was a closeted gay teen when this movie came out. I wanted to go see this movie but being from a small town I was worried what people would think. I went to see the movie with a cousin of mine and I remember th groans and comments made when the two men kissed. I thought it was beautiful but didn’t want to make any kind of reaction. I still think of this movie as a important part of my life.

Chris

I remember this movie. It was a far cry from Boys in the Band, and way better for how gay folk viewed themselves.

Rusty66

We went to see Boys In The Band multiple times, simply because WE were up on the screen. Also, the cruising was FANTASTIC (chuckle).

jpcflyer

Thanks David and Barry. Great interview.

Rusty66

I was working as a typesetter at Update, San Diego’s regional gay newspaper, when we sponsored the San Diego premiere of Making Love.

I can’t say that I had a particularly positive reaction to it. Several of us on staff thought it was … “quaint.” I mean, who in L.A. EVER made love UNDER the sheets? (chuckle). And the other guy Michael Otkean tricks with … vaseline on the table? Ex-CUSE me? (chuckle) KY Jelly would have been old-fashioned enough.

I’m sure part of that attitude came from already being out, and having worked as the office manager of the old San Diego Gay Center and Update in the late ’70s-’80s.

avesraggiana

I’m just old enough to remember the old, old Gay Centre on Fifth and Robinson in Hillcrest. Went to my first “Men’s Coming Out Group” meeting there in late 1988. How very quaint it all sounds now. Great times though, and great friends too.

OzJosh

Yes, there are ways in which Making Love was (slightly) daring and (slightly) ground-breaking. Hollywood still wasn’t comfortable with gay characters unless they were utilised for shock value or comic relief. But theatre and TV was already starting to portray gay characters more sympathetically and Hollywood was rather lagging behind. This discussion of the film also rather self-servingly avoids the fact that the film is essentially the wife’s story, with the much-loved Kate Jackson as the woman who has her marriage torn apart by her husband’s affair with a man. The final shot is of Claire, left alone and devastated, not of the two men, together and fulfilled at last. Despite the pretence of being “modern” and forward-thinking, Making Love actually has the sensibility of a 1940s/1950s Joan Crawford movie. It’s really all about the long-suffering wife.

Doug

Exactly. I never understood why this was considered a “pro-gay” movie. The film was basically about a straight couple breaking up, and the last few minutes gave it all away… the music swelled, both of them looked at each other wistfully, and the audience was left feeling sad about what they “could have been” if the leading man hadn’t come out of the closet. I think at the time gay men were so starved to be recognized in a Hollywood film that they overlooked the real message.

Michael

“alone and devasted”? Not sure what cut of the film you saw OzJosh but it actually ends with Claire very happily married (her new husband is actually in the final scene with their son) and, such was Jackson’s subtle performance, making it clear to us she still loved Zach but understood it just wasn’t to be.

Eddie Jr

I watched Making Love when it first came out. When I started to watch I was thrilled…until Bart and Zack kissed. Several people then walked out. It hurt. Unfortunately for me, 20 years old at the time, that is what I remember of that first viewing.

Richard 55

Making Love was about a bisexual man who cheated on his wife.

If Hollywood is dragging its feet on depictions of male homosexual desire, it’s because it fears its power. It has the power to destroy feminism and girl power in general.

Movies are often audience-tested using homophobic, anti-male feminists in the audience.

hanfrina

… Remember interviewing Barry, a Buffalo, NY Native, when “Making Love” (ML) opened here in his hometown! The Theater, near the SUNY, Bflo. “North Campus,” was SRO. He was a pleasant person, sharing personal items about his Mother, who also had battled Breast Cancer like thee elderly female character in ML. Michael Ontkean plays the Physician who treated her. I was Upstate Editor for “The Connection Newspaper,” a Bi-Weekly Newspaper for thee LGBT Community based in NYC. My own Mother attended the Movie’s opening.