In a world that keeps trying to fit us into neat little boxes, let me introduce you to the trendsetting wakashū of Edo-era Japan (1603–1867), a group that decided the societal norms were as appealing as a three-week-old sushi roll.

The wakashū, which translates to “young companions,” were adolescents known for their unique gender presentation and their significant social and cultural roles. They emerged as a distinct social category, a “third gender,” separate from men and women.

Japan was seriously ahead of the contemporary dialogue on gender. These Japanese youths transitioned smoothly into a recognized third gender, unlike their Western counterparts, who often grappled with the awkwardness of adolescence.

Wakashū held a unique role in Japanese society, balancing delicacy and strength, aesthetics and practicality. They studied arts, including music, dance, tea ceremony, and martial arts. That’s right, these chaps were as comfortable wielding a samurai sword as a calligraphy brush.

The youths lived the golden life within Japanese society. They were well adored and admired by fans across the gender spectrum, like teen pop idols that the entire family could get excited about. Both men and women found the wakashū alluring. Their charm was in the fluid way that they lived and dressed between Edo-era conventions of masculinity and femininity.

In Edo society, boys around 10 to 12 years old were considered distinct from males and became wakashū after growing their hair into an elegant topknot. This hairstyle wasn’t just a fashion statement. It was also a market of social status and identity. The half-shaved, half-long look was kind of like the mullet of the Edo period, but it somehow worked.

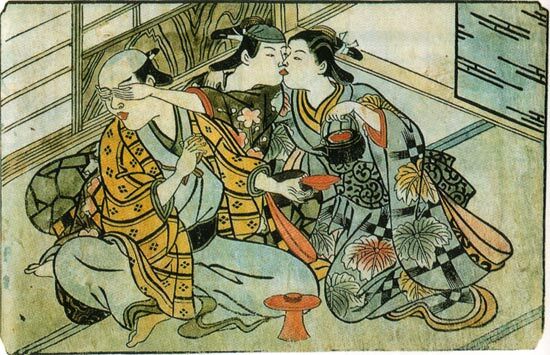

Wakashū wore sleeved kimonos with a deep tuck at the waist to suggest youth and vitality. Unlike men who shaved or plucked them, they kept their eyebrows full and bushy. Apparently, the ’90s learned nothing from the Edo-era about the value and social cool of a bushy brow.

Wakashū were not equivalent to modern gay men or transgender individuals–the concepts simply didn’t exist in the same way then. Nor did wakashū have the freedom to choose their roles entirely. They still had to abide by Edo-era norms. Yet, in their unique fashion, they were making waves in the waters of gender and sexuality.

This “in-betweenness” made the wakashū the apple of many eyes in the social fabric of Japan. Men and women both interacted with them. Older men would often take on a mentor role, which often included mentoring in martial arts or cultural practices. Some people even see wakashū as predecessors of modern LGBTQ+ identities in Japan.

The “nanshoku” or “shudō” bond ran deep, and the connection spanned many aspects of life, including physical intimacy. Far from being taboo, this was an accepted and respected part of society, a cultural norm alongside other Edo-era traditions.

We might chuckle a little at the image of a half-shaven lad balancing a samurai sword in one hand and a calligraphy brush in the other while trying to decide which senior samurai to woo. Still, they embraced their adored social position and leveraged it with aplomb. Wakashū may be centuries in the past, but the boldness, the fluidity, and the sheer swag are qualities we can aspire to today.

Unfortunately, as with most teen idols, the glamour eventually wore off. Around the age of 19, a wakashū would undergo the genpuku ceremony. Think of the ceremony as similar to a modern-day debutante’s coming out party.

This rite of passage marked the passage of the wakashū to adult manhood, marking the end of their androgynous phase. Adult men were then expected to pursue relationships with women, or with wakashū if they chose to continue the nanshoku tradition.

The concept of the wakashū complicates our modern understanding of gender, defying a simple binary. For centuries, many cultures have acknowledged a “third space” of gender that doesn’t neatly fit the male-female binary. Their existence serves as a poignant reminder that gender, as a social construct, has been perceived and lived differently across eras and regions.

So, why does the tale of the wakashū matter to us now? Beyond its inherent historical intrigue, it underscores the fluidity of gender and sexual norms, a topic that echoes loudly in our current societal dialogues. Recognizing and exploring these historical precedents can add nuance to our understanding of today’s LGBTQ+ narratives. Their story continues to captivate us today, not just as a curiosity but as a testament to how humanity has understood and expressed gender.

worship

This article is BS. Wakashu were considered young men, with their attributes, not a “third sex”. Utter nonsense; re-writing history for contemporary propaganda. . Pathetic. There is much to admire without misrepresenting wakashu.

worship

shu means boy. Waka shu means young boy. Shudo means the way of the boy.

It doesn’t mean a third sex. It means boy.

worship

Debutante’s ball? The coming of age when the adolescent is recognized as a man?

worship

Totally misrepresenting historical sexualities with modern jargon and categories is no help to anyone.

GlobeTrotter

I read a book about the Wakashu several years ago, but I don’t remember them being described as a third gender. A lot of ancient societies celebrated and even fetishized adolescent males, that doesn’t mean they were considered a “third gender”.