The following is an excerpt from Did You Sleep With the Models? by Sam Staggs, former editor of the gay magazines Mandate, Honcho, and Playguy. Read the book at samstaggs.substack.com

Arriving in New York in the mid ‘70s, I jumped into the fight for gay rights. That meant joining every protest demo in Manhattan, and each year in June marching up Fifth Avenue in the Gay Pride Parade. On less pyrotechnic days, I stuffed envelopes and proofread flyers at the National Gay Task Force. I wrote indignant letters to Time, Newsweek, the New York Times, TV networks, and other mainstream media when they ran homophobic articles. And they did so with metronomic regularity.

Then, in 1977, Alan Bell founded Gaysweek. At the time, according to Wikipedia, “it was one of only three gay weeklies in the world and the only gay publication owned by an African American.”

Alan rented office space in Chelsea and attracted a battalion of volunteers as writers, typesetters, photographers, advertisers, distributors. Against gargantuan odds, he kept the paper going until 1979. To cite a couple of his battles: Newsweek sued for trademark infringement, claiming that the title Gaysweek encroached both graphically and phonetically on its own trademarked title. Owing to pressure from the magazine, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office refused to register Alan’s publication. (Eventually it did so.) Weekly headaches included refusal by anti-gay printers to do the job Alan paid for; papers stolen from sidewalk boxes or vandalized; unpaid volunteers who, despite good intentions, couldn’t meet deadlines.

I first encountered Robert Mapplethorpe’s work on assignment for Gaysweek. The phrase “on assignment” sounds grandiose; my undertaking, however, involved no more than a visit to the Marcuse Pfeifer Gallery at Madison Avenue and Sixty-ninth Street. In June 1978 Marcuse Pfeifer–a native of Little Rock, Arkansas, whose unusual name suggested origins in Berlin or Vienna–mounted a historical survey of the male nude in photography, beginning in the nineteenth century although with emphasis on the work of such contemporaries as Peter Hujar and Mapplethorpe. Alan, in a typical frenzy of overwork, phoned to ask whether I could contact the gallery to obtain a press release and a representative photo for the paper.

Marcuse–a woman, I learned when she answered the phone–was happy to oblige. I chose a Mapplethorpe photo of a muscular black man seated, back to camera, on a round stool covered by a white cloth, with his head bent forward so that his broad right shoulder catches the light. Lower back and hips are in deep shadow. The photograph, sculptural rather than overtly erotic, ran in the paper without commentary other than gallery address, hours, and a few lines from the press release.

Meanwhile, Gene Thornton, in a priggish, sexist, homophobic New York Times review of the gallery exhibit, opined that “there is especially something to be said for old-fashioned prudery when the unclothed body is a man’s body…There is something disconcerting about the sight of a man’s naked body being presented primarily as a sexual object…The male nudes of Peter Hujar [and] Robert Mapplethorpe…inhabit a world that is closed to most of us, fortunately: a world in which men expose their bodies to strangers in a confused invitation to sex.”

This appeared on June 18, 1978–nine years after Stonewall, although to be expected in the Times, that paper of cultural taxidermy. I pictured Gene Thornton with lips pursed in distaste, typing angry words and protesting too much as he clutched a long cigarette holder while nervously fingering a silken ascot.

I don’t recall everything in the exhibition, but I reiterate that the photograph I chose for Gaysweek was hardly an “invitation to sex,” confused or otherwise. Already, however, unguessed by Robert Mapplethorpe, the bloodhounds had sniffed his trail, the pack was baying in the middle of “liberal” Manhattan, and Gene Thornton, like others of his ilk, bared angry fangs at men who expose their bodies to strangers in a confused invitation to sex.

How uninformed was this pack! How square! Those invitations were never confused, never confusing. They were either unambiguously sexual, or, like the Mapplethorpe photo above, artistic. And sometimes both. That’s what upset Thornton and those like him.

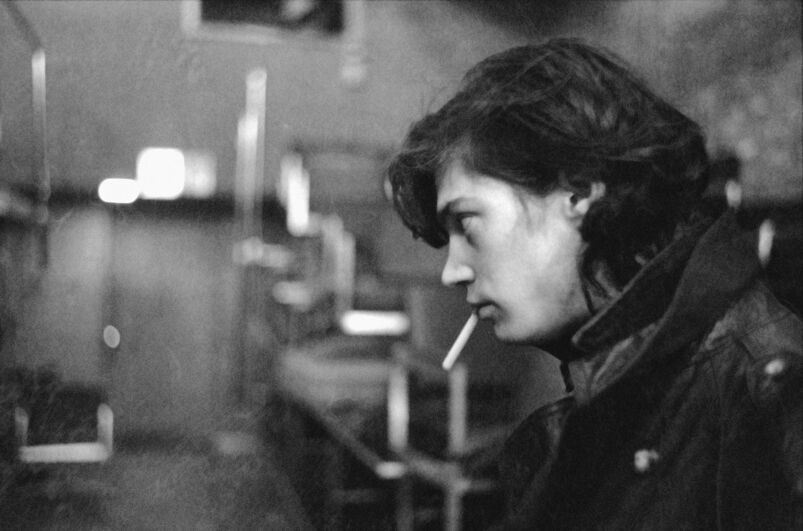

Fast forward from Gaysweek in 1978 to Mandate in 1984. I am now editor-in-chief and in that capacity always on the lookout for new material, especially art with a gay focus. My search took me to a gallery where I saw Robert Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Richard Gere. As one of the highlights in a show filled with striking images, the picture had as much to do with Mapplethorpe as with Gere–perhaps more. By that I mean that it did not begin and end as the picture of a pretty-boy actor. Gere, shirtless, was shot in profile. The play of light on his face, on long dark hair and on chiaroscuro-patterned skin, gave the picture a “classic” shape that alluded to the work of earlier artists such as George Platt Lynes, Edward Weston, even Julia Margaret Cameron’s famous photograph of the young Virginia Woolf. By shooting Gere in profile, Mapplethorpe avoided the actor’s close set eyes that give him something of a shifty look.

I telephoned the gallery for permission to reprint the picture in Mandate. The promised reproduction never arrived, and after several months I abandoned the project. A year or so later I saw the Gere portrait again. Since Robert Mapplethorpe’s phone number was on my Rolodex, left there by a previous editor, I called him to ask about the Gere photo, explaining that it was for Mandate‘s miscellany column, “Mandata,” where we reported on art exhibits, theatre, male and female newcomers to Hollywood and Broadway, and the like. I explained to Mapplethorpe that the image was in no way to be used in a sexual context. Rather, it would accompany a notice about Gere’s recent casting in the title role of the biblical film King David.

Mapplethorpe said he would need to obtain the actor’s permission. Whether this was a contractual obligation or a courtesy he didn’t explain. Nor did I risk sounding confrontational by asking whether permission was needed only in the case of Mandate but not, for instance, if the editor of GQ or Vogue had wished to reproduce the photo.

A few days later Mapplethorpe phoned to say that Richard Gere did not want his picture to appear in Mandate. The photographer didn’t elaborate; I did not press the issue. How odd, I thought, since Gere had won praise for his portrayal of Max, a homosexual incarcerated in a Nazi concentration camp in Martin Sherman’s play Bent, which ran on Broadway from December 1979 to June 1980. He told an interviewer at the time, “Yes, I’m gay when I’m on that stage. If the role required me to suck off Horst, I’d do it.”

Gere’s performance was shocking in the best sense of the word. I recall feeling discomposed for hours after leaving the theatre.

My two phone conversations with Robert Mapplethorpe regarding the Gere photo were businesslike and unmemorable. A year or so later, we met. Someone brought to my attention a would-be model with a spectacular endowment. This man was in New York for a month or so before his return to Italy. The race was on: can I nab him for Mandate before the other piranhas bite? Torso, owned by our publisher but kept in a lowly office across town like a back street mistress, was always on the prowl. Stallion, too, whose editor was a pleasant colleague, might hook the newcomer. The art directors and I agreed: send this specimen to Robert Mapplethorpe, whose increasing fame had not yet turned to notoriety.

After meeting the model, I wondered how Nero or Caligula–or Cleopatra–might have employed his Roman colossus.

Arrangements were made with Mapplethorpe, and in due course model and photographer met. The first mistake was color film. If only Robert had shot him in black and white, those photographs might still be shocking and titillating gallery goers and providing stimulation in the many books of Mapplethorpe photography. When I received the color slides, however, I felt as wilted as–well, as the model’s twelve inches, which drooped like one of the famous Mapplethorpe calla lillies left out of water overnight. There it lay, in subdued color not unlike a frame from Antonioni’s Il Deserto Rosso (Red Desert) — a monumental collapsed edifice needing the support of a flying buttress.

My hopes fell further as I shuffled the slides. The package contained fewer than the usual number, and in two minutes I knew that we could extract only an inferior, disappointing layout. Looking back, I suspect that pharmaceuticals, rather than f-stop or eros, dominated the photo shoot.

I consulted my associate editor, whose eagerness evaporated as quickly as my own. I expected a wrangle with the art directors, but they offered no more than a coordinate shrug. “Send them back,” Clif said as he breezed out of my office. Since he had a vague acquaintance with Mapplethorpe, I called after him, “Hey, what if you told him these don’t work?”

A sly smile, a shake of the head, and he was off for lunch and a few happy puffs as dessert.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s studio was located at 24 Bond Street, a ten-minute walk from our offices on lower Sixth Avenue. I half expected prima donna outrage at my audacity in refusing his work. I had sometimes encountered anger from disappointed contributors. I phoned, and in diplomatic language explained that despite my admiration for his work, the photos were not quite right for us. I blamed it on the detumescence. And no, I didn’t use that word; I saved it for today. I said, “It’s a magnificent d*ck, no argument there. It would be terrific for Playgirl’s soft-core style, but you know us — we need a raging hard-on!”

He laughed.

“Shall I send your slides back by messenger?”

“No, I’ll pick them up.”

Will there be a scene? I wondered. A time was set, the receptionist announced him, and he appeared. He was in his late thirties, but looked boyish and not at all the wild-eyed, demented hooligan of some of his self-portraits. His build was slight, he seemed a little shy, we shook hands, I said, “I’m glad to meet you at last. I’ve admired your work around town.”

“You probably thought I’d be a bitch, didn’t you?” He caught me off guard.

“No — I mean, yes, I couldn’t help wondering.”

“Well, am I?” Suddenly he was like a clever boy of twelve out to charm teacher after some naughty prank. Except that he couldn’t sit still, the result of cocaine, though I didn’t quite realize the source of his restlessness at the time.

How on earth do you answer such a question?

I looked him in the eye and said, with a certain stagey extravagance, “But Robert, you’re an artist, and no artist could be a bitch.” Then I added, “I confess I was worried that you might not understand. I appreciate your generosity. Please — let us use your work in future. I’ll send you another model. In fact, I have one in mind who…”

He stayed fifteen or twenty minutes, we chatted about his upcoming gallery exhibitions, I showed him around the art department and bestowed copies of our latest issues, and walked him to the elevator. “Thanks again for being a sweetheart,” I said. We hugged, and I never saw him again.

Gazing across the years, I scold myself. I should have used those pictures. If I had known his future trajectory, had I forseen the persecution, I would have grabbed up a photo of anything — even a crack in the sidewalk taken by Mapplethorpe.

No distinction resides in being the only editor in America to have rejected a Robert Mapplethorpe exclusive. Only regret.

Sam Staggs is the author of eight books, including All About “All About Eve”: The Complete Behind-the-Scenes Story of the Bitchiest Film Ever Made (2000); Close-up on “Sunset Boulevard” (2002); When Blanche Met Brando: The Scandalous Story of “A Streetcar Named Desire” (2005); Born to Be Hurt: The Untold Story of “Imitation of Life” (2009); and Inventing Elsa Maxwell: How an Irrepressible Nobody Conquered High Society, Hollywood, the Press, and the World (2012), all published by St. Martin’s and all in print.

His latest book, Finding Zsa Zsa: The Gabors Behind the Legend, was published in 2019 by Kensington Books. (Audio version read by the actor Paul Boehmer for Blackstone Audio.) This biography has been optioned by Amy Sherman-Palladino, writer/producer/director of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel”, for a film or miniseries. (Blackstone has recently brought out All About “All About Eve” and Close-up on “Sunset Boulevard” on audio.)Staggs’s work has appeared in a number of anthologies, including The Best American Movie Writing 2001 and Vanity Fair’s Tales of Hollywood (2009). His earlier journalism appeared in Architectural Digest, Vanity Fair, Opera News, Publishers Weekly, New York, Artnews, and a number of travel magazines.

morgan

I just checked out this chapter on Substack.com and found all kinds of pictures not given here, several by Mapplethorpe and some from other sources. Its more interesting than this escerpt. I have subscribed to the author’s post.

Invader7

Mapplethorpe was fricking awesome ,amazing, scandalous, shocking ,amazing and rare. One of a kind. And one of us !!!

inbama

He was groundbreaking, brilliant and dangerous.

A GAY man definitely worth celebrating.