Welcome back to our queer film retrospective, “A Gay Old Time.” In this week’s column, we revisit 1980’s Cruising, the highly controversial crime drama set in New York City’s gay leather scene.

Last week, legendary director William Friedkin died at 87 years old. He left behind one of the richest filmographies in Hollywood history, helming all-time classics like To Live And Die In LA, The French Connection and The Exorcist.

Friedkin also left an indelible mark in the pantheon of queer cinema, directing not one, but two hugely influential (and controversial) films that were a landmark and turning point in how gay life was portrayed on screen: 1970’s The Boys in the Band, and the movie we will be discussing this week, 1980’s Cruising.

Much has been written, dissected, criticized and admired about Cruising and, in the over four decades since its release, its place in the discussion of queer representation in film keeps changing and evolving. This week we’re going to go a bit narrower and, in order to pay homage to one of the great directors, explore the cinematic tools Friedkin used to immerse the audience in the gay leather lifestyle.

The Set-Up

Cruising takes place in 1980s New York City, where a serial killer has been hunting down and murdering gay men. He frequents leather bars and popular cruising spots, where he picks up men, takes them back to a private spot, ties them up and brutally kills them. The head of the police asks Detective Steve Burns (Al Pacino) to go undercover into the gay leather community to investigate and track down the killer.

As Burns goes deeper into this “underworld” and learns how men move in and out of the shadows (and follows them there), he experiences firsthand the discrimination and prejudice that the community faces (often from cops like him) and starts noticing his own guard coming down and his persona changing. And that’s for better or for worse; depending on your read of the famously open-ended ending.

Cruising Into A Grey Area

Cruising faced great backlash from the gay community when it was released for the way the movie linked fetish with violence, and Burns discovering his own repressed desires with the implication that he may have been involved in the killings. Paired with the rising anti-gay sentiments that were about to be compounded amid the AIDS epidemic over the next decade, it’s easy to see how the movie’s morally grey themes were perceived as thorny at the time.

A whole other discussion can be made about whether these themes and ideas hold up better today. But what is clear revisiting the movie now is the distinct purpose with which Friedkin painted the “other world” that Burns goes into: how it is portrayed, both in the story and the framing itself, as something new; something threatening and yet deeply alluring. How he captures the simultaneous sense of danger and arousal that permeates those bars, those alleys, those anonymous encounters. Those things have remained timeless.

Related:

How ‘American Horror Story: NYC’ cribbed from 1980’s controversial erotic thriller ‘Cruising’

If the latest season of ‘American Horror Story’ looked familiar to you, there’s a good reason why.

Shadow World

Friedkin does a pretty stark differentiation between the “real life” and the “cruising” spaces, mainly using shadows. When Burns enters the leather bars, or wanders the park among nameless men, or we see the encounters that lead to the murders, everything and everyone is partially covered in darkness. We aren’t able to see the full picture. We know something (or someone) is hiding, and may be watching.

This purposeful concealing works both to illustrate how gay men had to live their lives half in darkness, but also the ever-present feeling that danger is always lurking nearby.

The Gay Gaze

Friedkin also understood the power of the gaze; the importance of watching and being watched in the world of cruising (in both the double entendre meanings of the title: looking for sex and patrolling the streets). Back in a time with no hookup apps at hand or the freedom to openly approach someone, it all started with a look. It still does—if you go to the right places.

Every time Burns is at a bar, especially towards the beginning where he’s taken the role of a passive observer, the screen fills up with close-ups of men looking directly at us. Eyeing us up and down. Looking for a hanky in our pockets. Desired, lusted over, cruised. The movie translates the equally transgressive and exciting language of the act, and puts it on display on screen.

Related:

Queer Fatale: 10 sexy, gay erotic thrillers to titillate and palpitate

You won’t be able to look away.

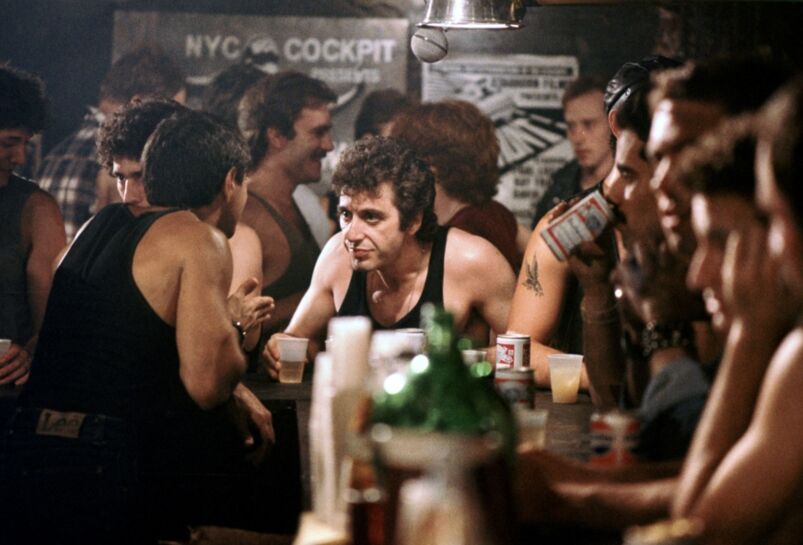

Sweaty, Free, & Happy

It is also very interesting that, despite the criticisms about how the movie connects the gay world with the murders, Friedkin makes sure to paint the bars, the parks, the side streets, and any other space where gay men are together as something communal and full of life. The police precincts, Burn’s apartment that he shares with his girlfriend Nancy (Karen Allen), and practically every other space in broad daylight is usually empty, colorless, and silent.

Queer spaces always have music playing, even the dingy alleys or secluded parks. Men are in close proximity, usually making out or licking some body part. They are sweaty, free, and happy.

When Burns tries poppers for the first time, and lets himself go on the dance floor, the entire composition of the shot completely changes. With a literal enlightenment, Burns is able to see and understand why men risk their lives every night being down in that basement.

Our Scene On Screen

And Friedkin understood that, too. He knew how sacred the dance floor in a crowded bar is. He learned the language that men had been using for decades to find each other, and was able to translate it into the visual language he mastered. He got the perfect balance of danger and thrill that comes with following an unknown man through the shadows. And maybe he weaponized that as well.

But despite the criticism—and on top of the accolades that the movie has gotten through the years (and will continue to do so) as one of the boldest portrayals of gay life in a mainstream film—it could never be said that Friedkin did not do his homework. Rest in peace.

Cruising is available for digital rental or purchase via Amazon Prime Video, AppleTV, Google Play, Vudu, and YouTube TV.

Related:

Relive the erotic 1980 thriller ‘Cruising’ with this fun new children’s playset!

Now your kids can relive the excitement and danger of the ’80s New York City leather bar scene right in your own home!

JTinToronto

Has anyone ever attempted a remake of Cruising? Wonder what it would be like to be redone now. Would it be really raw and raunchy or total cheesy. And who would play the lead part? I vote for Richard Madden.

Kangol2

Did James Franco tinker with part of it in Interior. Leather Bar. back in 2013? He tried to recreate the lost and missing 40 minutes of explicit footage, but it came off as a bit meh. The leather bar scene in the US today is very different from 1980, though, so it’d probably need to be reimagined and updated.

dbmcvey

The movie’s a mess and the book is even worse.

There was a season of AHS that was pretty much a remake.

monty clift

It would be accused of not being politically correct enough, but this time by the gender-confused community, as you have seen with all the other gay reboots.

dbmcvey

Monty, your obsession with trans people is psychopathic.

ScottOnEarth

Thanks for this review. I have never heard of this movie but will definitely check it out…and Jorge Molina is an excellent writer.

SUPREME

it’s well worth watching. i liked it a lot. i don’t see why people had a problem with it.

abfab

Because watching a naked man, spread out, flat on his stomach, face down, restrained to a four-posted bed, expecting to be f u c k e d only to be stabbed mutilple times is not eveyone’s cup of tea.

Kangol2

It was a landmark, highly controversial film that sparked protests in NYC and other cities.

theaterbloke

I read the book Cruising is based on and it is a very different animal. The police officer, John Lynch, was one of many assigned to go undercover in pursuit of the killer. And I don’t recall it taking place in leather bars much, if at all. The main thrust of the plot was that the killer was filled with self-hatred and targeted gay men who looked like himself, of which John Lynch was one. In the end I believe he went on a rampage through a bathhouse and ended up dead. At that point, Lynch, consumed with his own emerging queerness and self-hatred, most likely became a copycat killer, starting with his upstairs neighbor who likewise fit the profile. This led the family of the original killer to sue the police department claiming that they had gotten the wrong man and were defaming him him since the murders we’re still taking place. It was a decent crime novel, only bearing a scant resemblance to the movie that was made. Supposedly it was loosely based on a real case, but I don’t know any of the details about that.

KyleMichelSullivan

I was in NYC at the time this was being shot so read the book to see what all the uproar was. Your memory is pretty dead on. What angered me at the end of the book was how a medal was pinned on Lynch for some reason or other. It came across as if rewarding him for killing his gay neighbor and ignored that he’d also killed a cop. I think the community was afraid the film would be close to the book — congratulations for killing a queer kind of thing. I’m pretty sure that wasn’t the intention of the author, but that’s how it came across, to me.

I never did see the film. By the time it came out, I was in Austin and I think it only played for a week.

Jim

LOL the movie captured Hollywood’s skewed view of the world

barryaksarben

it was an honest depiction of the leather bars, It. was being filmed as AIDS hit so the comm unity was being attacked all over and. many felt this was an attack. I viewed it as a film about a murderer in the gay community which had just happened in the NYC leather community a few years earlier

FreddieW

I’ve never watched it, although Al Pacino is one of my favorite actors. The clip in “The Celluloid Closet” was enough to convince me not to watch. I don’t like disturbing serial killer stories.

eeebee333

I was in my early 20s when “Cruising” came out, and I saw it in the theatre. I always thought it was unfairly maligned by critics and crybaby gay activists.

abfab

Yes, sweetie. It was so terribly unfair.

dbmcvey

No, the maligning was fair. At this point we can look at it from a different perspective but at the time it was one of the few representations in mainstream movies.

abfab

The Very Best Crime Films With Al Pacino, Ranked 1-16

Cruising ranked 16. Not his best, obviously.

abfab

Let’s talk about Friedkin’s, ”The Exorcist”. Regan was a Lesbian. Tough. Real tough.

dbmcvey

It’s an interesting movie but it’s a huge mess. If you listen to Friedkin’s dvd commentary it’s clear everyone was on drugs.

bachy

I have serious difficulty with films that combine sex (vulnerability) with brutality and murder. Watching such scenes, I’ve come to feel myself to be the victim of a sadistic vision, in which I and the paying audience willingly play the role of the masochist. I inevitably come away with some kind of psychic wound.

abfab

I feel the same way. It made me think about Looking For Mr Goodbar. Although The Sopranos…those people all deserved what they got.

Diane Keaton won the best actor Oscar for Annie Hall that year and was also nominated for Good Bar.

inbama

Compared to Ryan Murphy’s “American Horror Story” take on the same subject, it was practically “The Sound of Music.”

dbmcvey

The Murphy take was more an allegory. This movie is a huge mess narratively though. If you listen to Friedkin’s commentary, they were making it up as they went along.

inbama

Pacino in leather was about as sexy as Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic nose.

Man About Town

I thought the movie was a mess, especially the cop-out “open” ending. I kept waiting to learn who the killer was and you never do! I decided it was probably the Richard Cox character but it might also have been Pacino’s character but who knows?

Friedkin does get points for consistency because the whole film seems incoherent, so why shouldn’t the ending? And why does it end with the girlfriend trying on the uniform? It seemed like some kind of message but what that message was is anyone’s guess.

abfab

Talk about a B Movie…..

peluzo

Love B movies

john.k

I saw the film when it came out first. I found it interesting as it portrayed a world I was not then familiar with. It was filmed in actual gay clubs. There is one scene where you can see that a guy in the background is being fisted. It’s not explicit but there is no doubt what is happening. I noticed that on a second viewing. I don’t think I did the first time.

winemaker

Many of the interior scenes of Cruising were filmed at the Mother Lode a gay bar on Santa Monica Blvd. near Robertson Blvd. in West Hollywood. The bar attracted a mix of clientele and wasn’t specifically a leather bar. For that experience you had to go deep into Hollywood and Silverlake for real leather bars. On a couple of the walls of the Motherr Lode, there were large blow ups of photos of the skip, a gondola that took the miners down the ‘hole’ to the shafts and tunnels of the Empire Mine, one of the oldest and richest hard rock gold mines in Grass Valley California that operated from 1856 – 1956.